Out of the darkness, the Alps emerge. Highlighted by Romantic literature, the mountains are about to open their hearts to man. Under the lyrical pen of the great writers, the mountains shine and shine. A new era begins in the celestial kingdom. After exploring the genesis of Alpine stories, in this second instalment I take you on a tour of the Alps in literature during the golden age of Romanticism.

The Alps in Literature: In the Golden Age of Romanticism

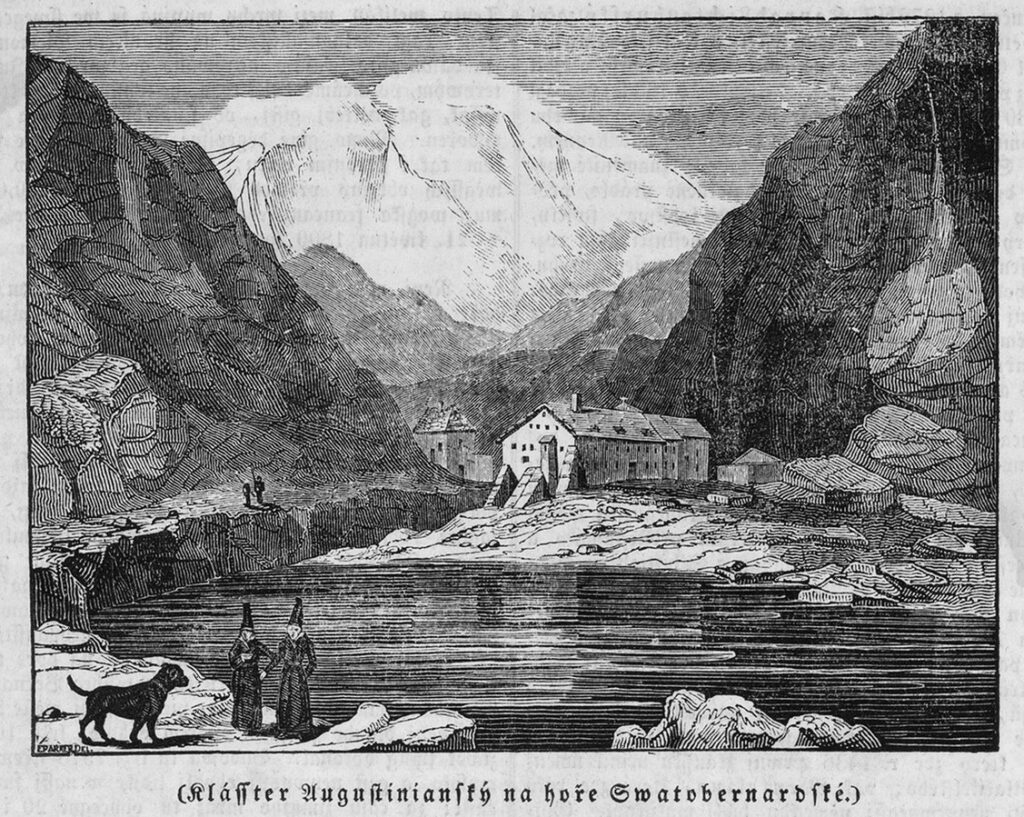

In the 19th century, the Romantic movement took off. From a threatening realm, the Alps became a place of the sublime. Their dizzying peaks and eternal ice transcend fear to embody grace. Greatness of soul and absolute beauty. In his novel Oberman, published in 1804, Étienne Pivert de Senancour evokes the mountains as a place of recollection, far from the torments of the world. A precursor of the climbing narrative, the author guides us with unprecedented precision along the crests of the Dents du Midi. From Saint-Maurice, he reaches the foot of the massif alone, at an altitude of 2,500 metres. His words convey his joy and dreamy thoughts. And as night falls, he describes the horizon that opens up before him: " The air is cold, the wind has ceased with the evening light; all that remains is the gleam of ancient snows, and the fall of waters whose wild rustle, rising from the abyss, seems to add to the silent permanence of the high peaks, and the glaciers, and the night. "

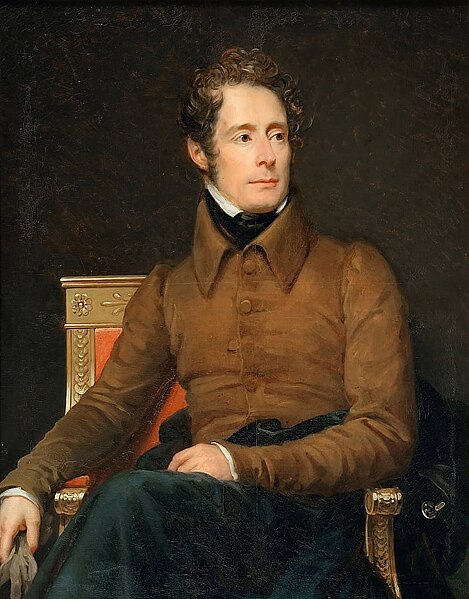

Lord Byron, too, pays tribute to the omnipotence of the high mountains: "Above my head / Are the Alps, the dwelling place of the tempest; / Nature's palaces, immense arsenals / Whose vast ramparts raise their battlements, / Their whitish summits, above the clouds, / Where lightning and storms break; / Vaulted thrones of ice and eternity, / Where avalanche and untamed lightning roll! / All that strikes the soul, enlarges its power, / On these vast heights seems to take birth, / As if to indicate how proud and vain are humans, / Compared to these mounts."(Le Pèlerinage de Childe-Harold, Canto III, LXII, 1816. Translated into verse by Georges Pauthier in 1828) A poet emblematic of the Romantic era, he saw the Alps as a haven of peace.

In Book VI of his poem The Prelude, published in 1805, William Wordsworth sets out a primordial duel: man's humility in the face of immensity. An indomitable nature against which we can do nothing. But if the mountain surpasses us, can we really not rise up to it? In his 1817 poem Mont Blanc, Percy Bysshe Shelley finds in contemplation the means for man to unite with the grandiose. The high mountains open up a parenthesis of eternity at the heart of his fleeting life. Alphonse de Lamartine also sees the wilderness as a mirror of our state of mind. In his 1836 poem Jocelyn, the ardor of love echoes the impetuous splendor of the Dauphiné Alps. In the mountains, dazzling and implacable, lies the very essence of life. This is how the philosopher and writer Friedrich Nietzsche saw the heights as a metaphor for spiritual elevation and self-transcendence. When he wrote his famous book Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra) in Sils-Maria, he drew his inspiration from the grandeur of the Swiss Alps, believing that confronting one's suffering during an ascent leads to serenity: "He who climbs the highest mountains laughs at all tragedies, whether real or not.

The Alps in literature: When the poet becomes a painter

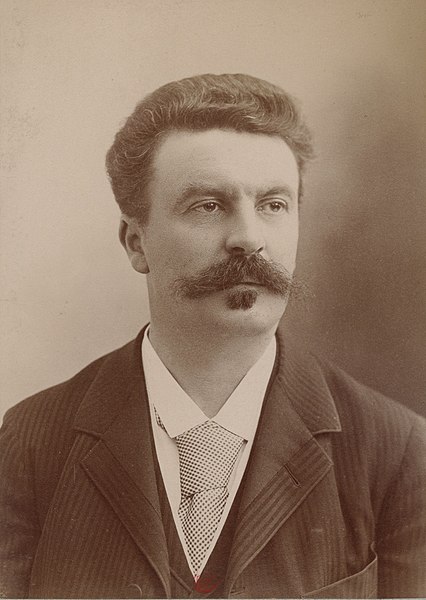

The Alps were clothed in light by Romantic poets. A source of tranquility, they also inspired writers to write colorful descriptions. When Guy de Maupassant evoked Dent Blanche in his short story L'Auberge in 1886, two words were all he needed to paint a portrait. Thanks to the author's talent, this mountain in the Swiss Alps is transformed into a "monstrous coquette", and everyone immediately imagines the silhouette of the creature.

In the age of Impressionism, Théophile Gautier depicted mountains with a colorist's eye. In Chapter II of his story Vacances du lundi. Tableaux de montagne, published in 1881, see how glaciers are brought to light: "pearl gray, lilac, cigar smoke, China rose, amethyst violet... an ideal blue, which is neither the blue of the sky, nor that of water, which is the blue of ice." Through the magic of words, he leads us into a world of a thousand wonders. In all its nuances, he highlights the pictorial beauty of the Matterhorn at sunrise: "The icy serenity of the sky was tinged with bluish steel, like a polar sky, and at its edge it was strangely indented by the dark silhouettes of the mountains forming the horizon circle. Above these indentations, the gigantic peak of the Matterhorn jutted out with a desperate thrust, as if it wanted to reach out and pierce the blue vault." He knows that the mountain carries chaos within it, but its beauty captivates us, its sheer scale fascinates us. And here we are, among those who will be forever in love with it.

The Alps in literature: On the borders of romanticism and ignorance

At a time when Romantic literature is singing a hymn to the mountains, one writer is exploring the opposite path. In his Voyage au Mont Blanc, François-René de Chateaubriand feels crushed under the weight of the high summits of Chamonix. He lacks the distance to admire the landscape, and blames the Alps for making him feel so small. The sheer size of the mountains hurts human pride. They become ugly under his virulent pen. He compares the Mer de Glace to "lime and plaster quarries". Feeling trapped at the "bottom of a funnel", he deplores the fact that summits "blacken everything around them, even the sky, whose azure they darken".

But in the end, don't we have to face the peaks to appreciate their brilliance? There's nothing like an encounter to discover yourself. For the beauty of the mountain is so inconceivable that it can only be grasped by climbing it. It is through contact with its flanks that it reveals itself to man. When Alfred de Musset wrote his poem Au Yung-Frau in 1829, it was only the name of the mountain that inspired him. The Jungfrau, or "young girl", is part of the art of metaphor. But the author is far from translating the pure, eternal essence of the summits Alps into verse.

Stendhal bears witness to this in Mémoires d'un touriste, published in 1838. " We are in the middle of the greatest Alps, but [...] precisely because I have admired so much [...], I no longer have the strength to write and think. All I come up with are graceless superlatives, which paint nothing to those who have not seen, and which revolt the reader who is a man of taste. " You have to measure yourself against the mountain to celebrate it. And only those who have experienced its sovereignty can paint its portrait.

The time has come to leave the pen to the greatest mountaineers. Drunk with adventure and new challenges, they brave the mountains in search of the absolute and the truth. And so begins the third part of our literary adventure in the high mountains.