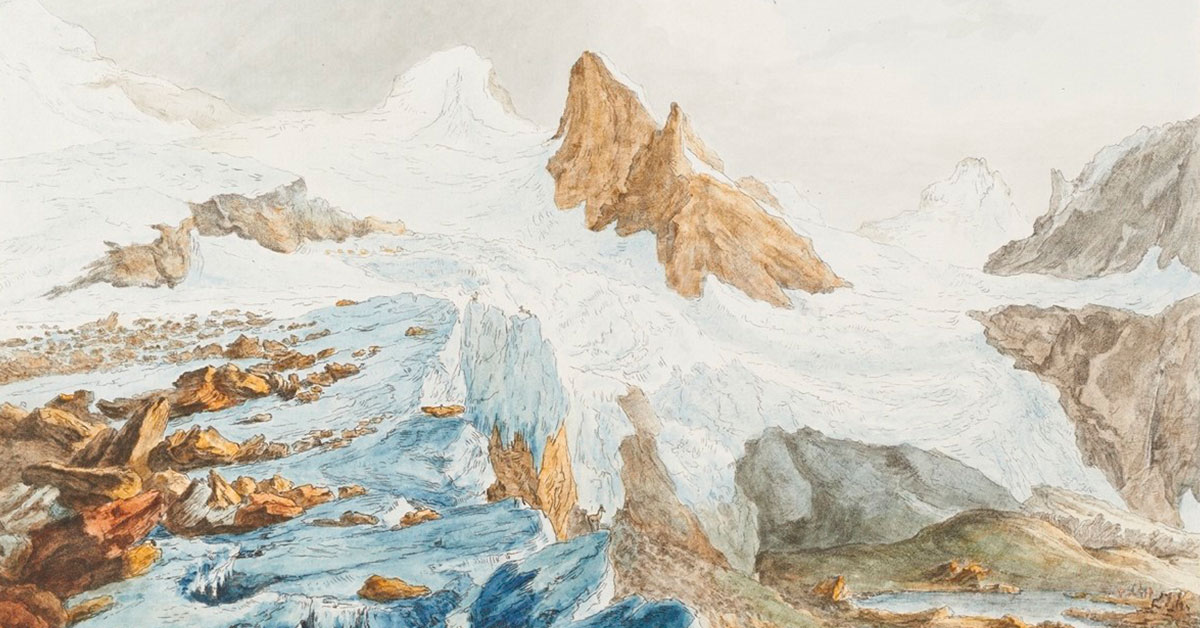

Caspar Wolf (1735-1783) was one of the first artists to travel and paint the Alps between 1774 and 1779. Although he painted other subjects, it is precisely as a painter of the Alps that he has passed into posterity. His contemporaries already emphasized Wolf's innovative side, like Karl Gottlob Küttner in August 1778:

Wolf is the painter of the sublime and terrible nature of the Swiss mountains. He went deep into the icy and snowy regions of the mountains, as no painter had done before; no danger, no difficulty could prevent him from exploring the most awful nature in its hidden heights and abysses, nor from drawing and painting, even in winter and in the middle of the snow.

The Remarkable Views of the Mountains of Switzerland

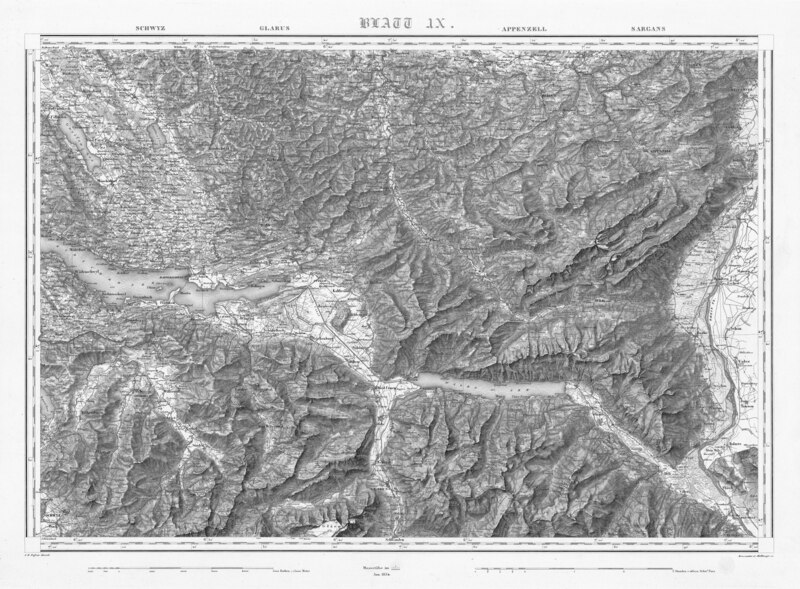

Caspar Wolf trained in southern Germany and later in Paris, where he was a pupil of Philippe de Loutherbourg, an English painter best known today for his painting of an avalanche. In 1773, back in Switzerland, the Bernese publisher Abraham Wagner gave him the most important commission in 18th century Switzerland: a set of 200 paintings of the Alps. From these paintings would be drawn prints illustrating a book, Les Vues Remarquables des montagnes de la Suisse. The different texts are about the natural curiosities and beauties of Switzerland - Wagner insists on the beauty of Switzerland in his introduction -, mainly the mountains. Between the texts and the engravings, Les Vues Remarquables is a kind of travel guide before its time.

The project is placed under the patronage of Albrecht von Haller, famous for having published Die Alpen in 1732, a poem that was a resounding success and that went through several different editions in the 18th century. The Bernese pastor and scientist Samuel Wyttenbach provided the scientific perspective. He was in contact with the greatest scientists of his time, including Saussure, famous for his Voyages in the Alps and for having offered a reward to anyone who succeeded in climbing Mont Blanc.

Like Wagner, Haller shows a concern to make the most remote and least accessible beauties of the Swiss Alps, especially the glaciers, accessible even to people who could not travel to Switzerland. From then on, the accuracy of the representation becomes crucial and is reflected in the contract between Wagner and Wolf: although it has disappeared, we know that the publisher asked the painter to produce paintings that were topographically accurate, yet artistic.

Travelling in the Alps and painting in the open air

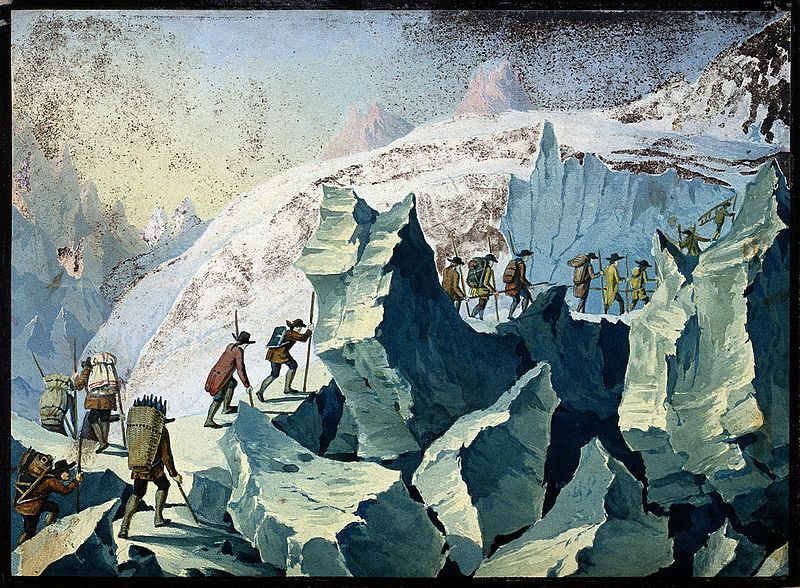

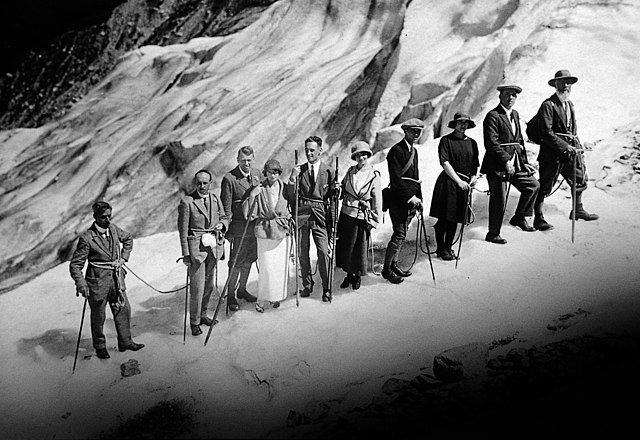

In order to fulfill this commission, Wolf had to travel to the Alps several times. He traveled at least a few times with Wagner and Samuel Wyttenbach. Unfortunately, we do not know exactly what these trips were, but Wyttenbach's writings document at least the one in 1776 and give us an idea of what an undertaking this was at the time. Caspar Wolf painted his oil studies on the spot, a relatively common practice among landscape painters of the time and one that goes back to the seventeenth century: several French painters of the French School in Rome did so. But there is a notable difference between doing it in the Roman countryside and in the middle of the glaciers, at 2600m altitude.

Several of Wolf's studies have come down to us. By comparing them with the final painting, one can see that most of the artistic choices were made on the spot and that the study already contains the final work. Wolf painted the picture back in the studio based on his oil study. In some cases, Wolf would return to the site with the painting, with the help of a porter, to make some corrections to the motif, especially in terms of light.

The Wagner firm in Bern

The paintings were exhibited in Bern in Wagner's house in alternating vertical and horizontal formats to break up any monotony. They were not for sale, but it was possible to order another variant from the painter, either in oil or in another medium. This explains the few cases where two different versions of the same painting have come down to us. Wolf also sometimes depicts the same scene twice, once in calm weather and once in stormy weather.

Geological interest

Wolf was also particularly interested in caves and depicted several of them, both in the Alps and in the Jura. The bridge is also a recurring motif in the work of Caspar Wolf. The viewpoint is often located near one of the bridge bases, with the bridge "framing" the landscape, a habit reminiscent of the engravings of the Italian Piranesi. Waterfalls are another recurring motif in Wolf's Alpine work. Among these is the Staubbachfall in Lauterbrunnen, which was already a great attraction in the 18th century: Goethe, for example, mentions it on his travels in Switzerland.

Aesthetics of Caspar Wolf

Wolf always modifies the landscape slightly: he accentuates the height of the mountains, compresses the landscape in width, brings the mountains closer together. In spite of all these changes, it is still easy to recognize the landscape. Wolf's paintings can even be used for search scientific purposes, e.g. to find out the state of the glaciers in the 1770s. Wolf often depicts himself as a painter in his paintings. This is a way of emphasizing that he actually visited the site and that the painting the viewer is looking at is therefore true to life. These figures in the landscape are also a way of introducing the viewer to the landscape and giving an idea of scale. Some of the paintings, however, are pure landscapes. Wolf's paintings are part of the aesthetics of the sublime, that feeling of delicious horror caused by the awareness of danger and the immensity of nature. The painting of the Devil's Bridge is emblematic: a few men pass over a bridge that seems very puny in the face of the impetuosity of the Reuss and in this particularly arid and hostile setting.

An exhibition in Paris

The Remarkable Views were republished between 1780 and 1782 in Paris. It is the French engraver Janinet who takes care of the engravings, the four-color prints (the engravings of the first edition are hand-colored with watercolors), technique of which Janinet was a master and which justified the trip to Paris. Wolf and Wagner took the opportunity to exhibit the paintings. But it was a failure, as the Parisian public shunned the exhibition. To avoid a fiasco, Joseph Vernet, an important landscape painter with whom Wolf had trained in his youth, bought five works. The Paris exhibition reveals how innovative Wolf's painting was for its time, especially for the urban public.

Posterity of Caspar Wolf

Wolf's paintings were forgotten in a castle in Holland at the end of the 18th century and were only rediscovered in the first half of the 20th century by the Swiss art historian Willy Raeber. Several exhibitions have been devoted to this painter, who is now considered one of the first mountain painters, but also one of the precursors of Romanticism. Thanks to the engravings, however, Wolf had not been completely forgotten.