A youth marked by many bereavements

The life of the young Hodler was marked by many bereavements, beginning with the death of his father when he was only eight years old. His mother and all of his siblings followed a few years later, all of whom died of tuberculosis. This had a profound effect on Hodler's character, but also on his career: his mother remarried to the decorative painter Gottlieb Schüpbach, which allowed young Ferdinand to be introduced to the art of painting. He was later apprenticed to Ferdinand Sommer in Thun, who painted pictures of the Alps for tourists. He moved to Geneva in 1872, where he became a student of Barthélémy Menn. He continued his artistic training abroad, notably in Paris and Madrid.

The artist's mission

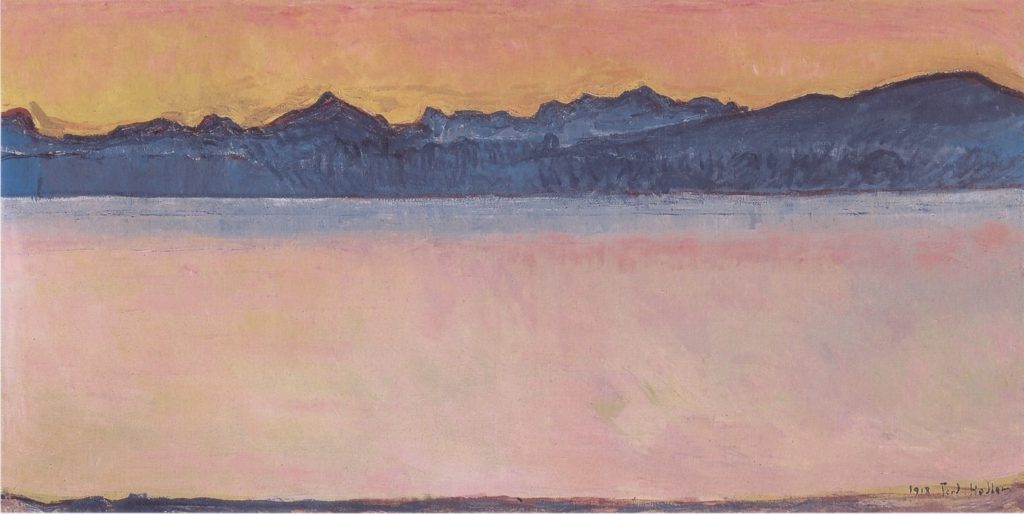

According to Hodler, the artist's mission is "to express the essential element of nature, its beauty, to bring out the essential beauty".

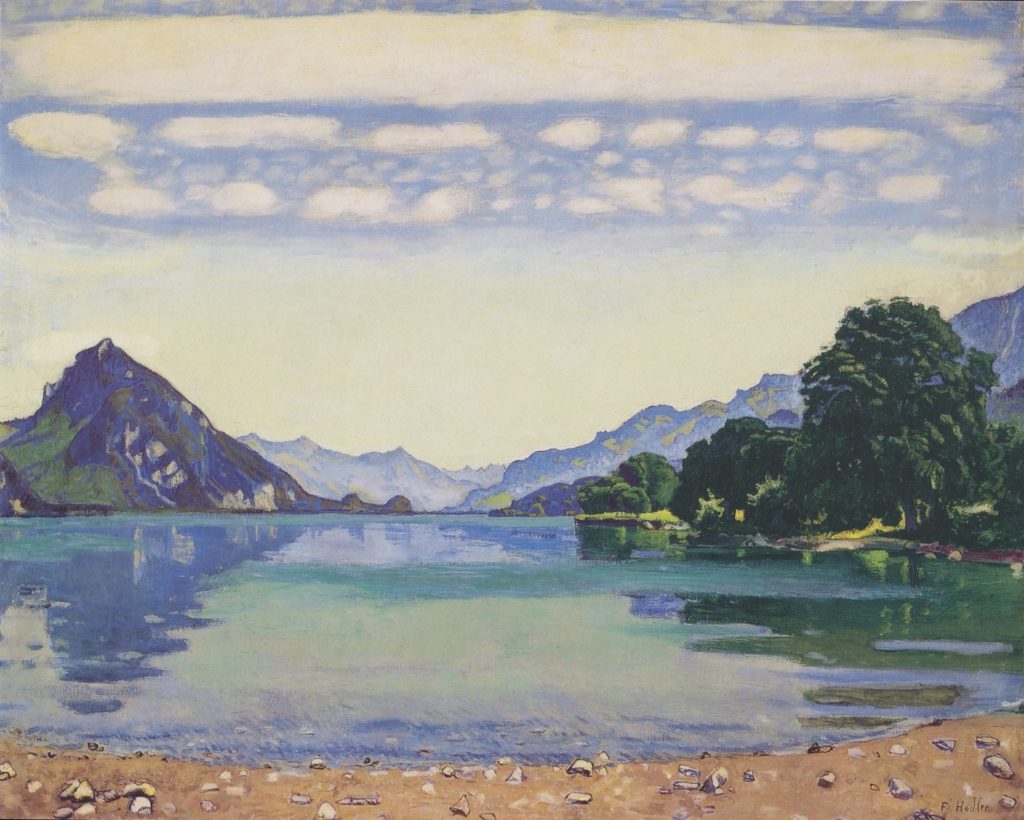

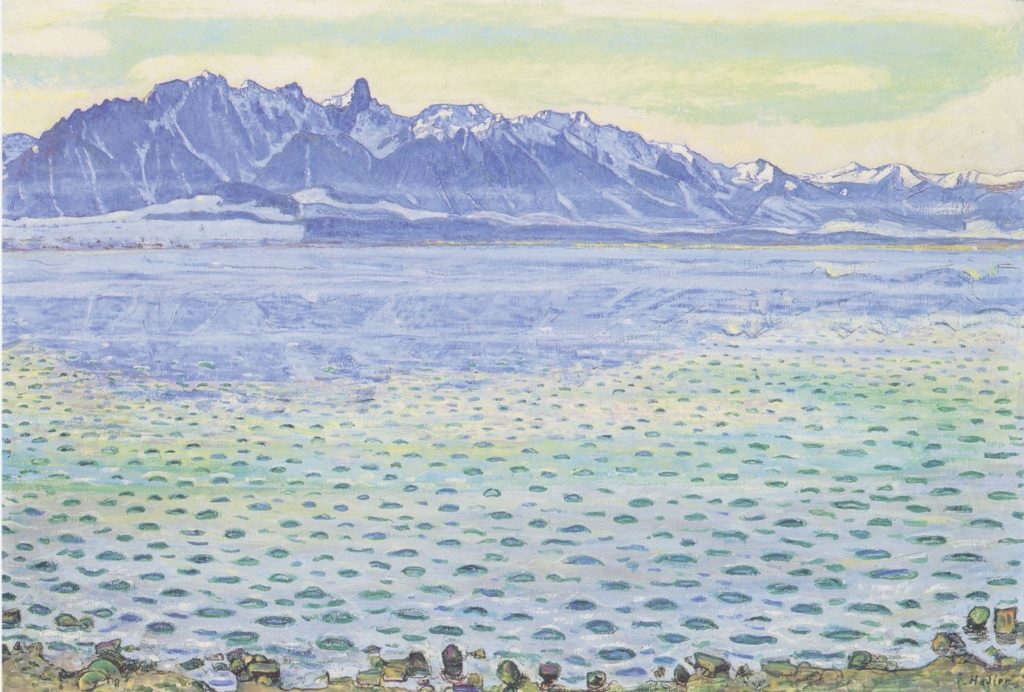

This conception of art will lead him to remove little by little any human figure, but also any element or superfluous detail. Only the essential remains, nature itself. This is also done through the light, often full and powerful, revealing the entire landscape, as in The Léman since Chexbres.

Symbolism and parallelism

Hodler believed that man is part of a universal law, of a great whole. He made this visible in his paintings by rhythmic forms repeating themselves symmetrically. Hodler spoke of parallelism. He introduced it in a painting in 1885, The Brothers' Wood, which he commented by saying that in a forest there is an impression of unity caused by the parallelism of the fir trunks. The parallelism is found in his landscapes from 1890. The parallelism is above all a choice of framing, but Hodler did not hesitate to slightly modify the geometry of the mountains if necessary. Thus, it is not uncommon for summits to be more pyramidal under Hodler's brush than it actually is.

Lake Thun with symmetrical reflections and Lake Thun from Leissigen are two paintings that make this clear. In the first, Hodler' s careful choice of framing enables him to create a picture that is in keeping with the principle of parallelism. Lake Thun from Lessigen, framed more broadly from much the same vantage point, is a quite different work, which clearly shows how parallelism works. Even more than the latter, Lake Thun with its symmetrical reflections conveys a suspended atmosphere out of time.

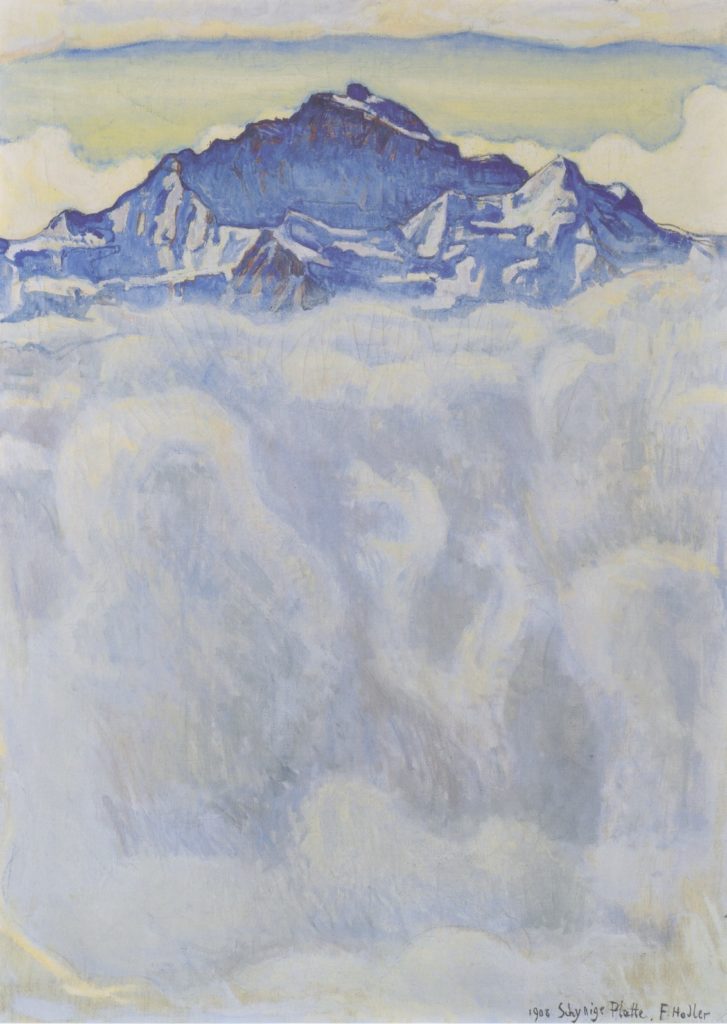

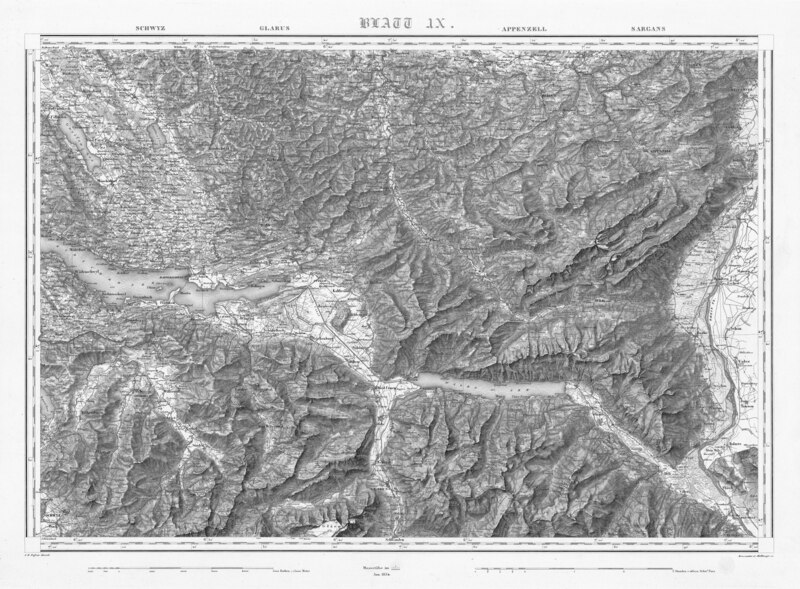

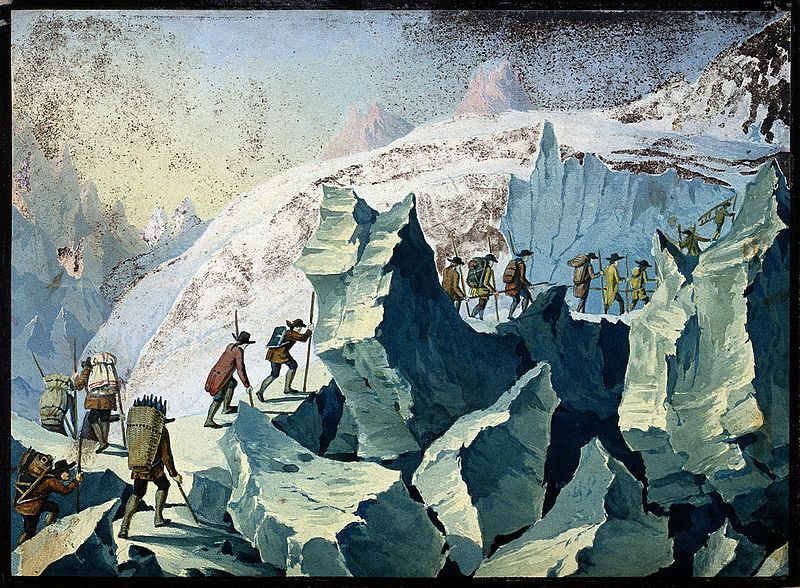

With the help of the mountain trains

Hodler benefited greatly for his painting from the development of mountain railroads. In fact, all of the viewpoints from which Hodler painted summits are located near a mountain railroad station or a funicular, which were developing rapidly in the last decades of the 19th centuryas we have seen elsewhere articles. Hodler painted several pictures from the Schynigge Platte, where the railway station was opened in 1893. The Jungfrau in the fog, painted in 1908, is one of these.

More foreground

The Jungfrau in the fog is an innovative painting: there is no more foreground, so essential to the composition of a landscape, and this since the Renaissance. The difficulty of finding an appropriate foreground had been a problem for several painters and photographers of mountains. To return to Hodler's painting, the Jungfrau occupies only a small part of the total composition and seems to float above the fog, above the sea (of clouds).

Some paintings give an ethereal atmosphere to the composition; the mountains then seem to be much lighter and almost float in the middle of the composition.

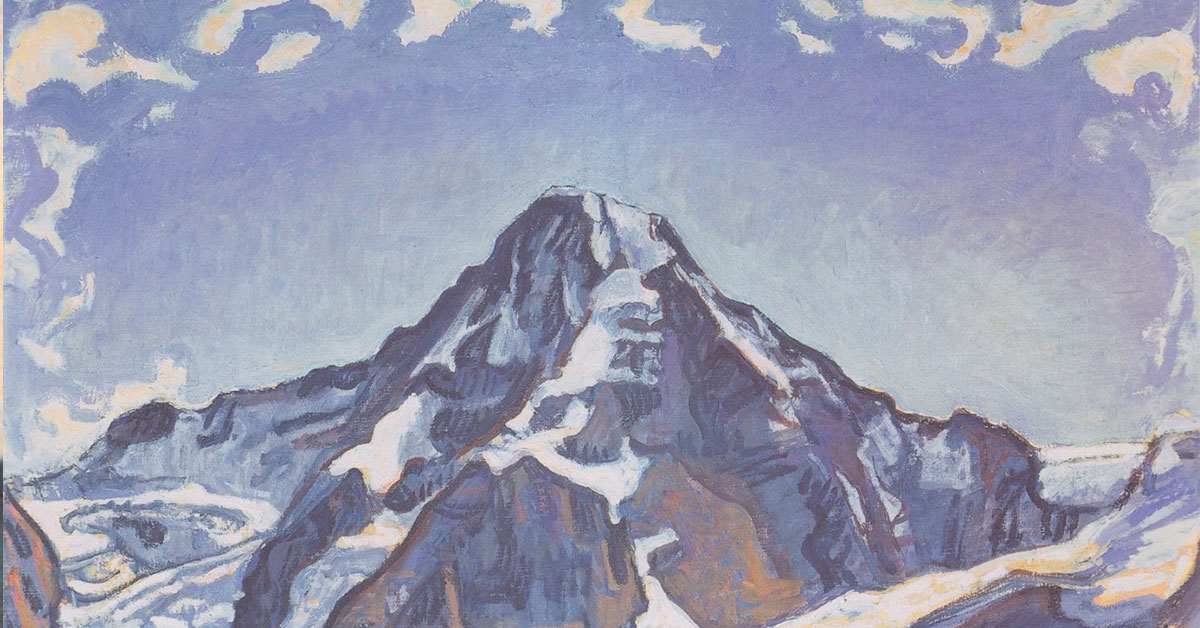

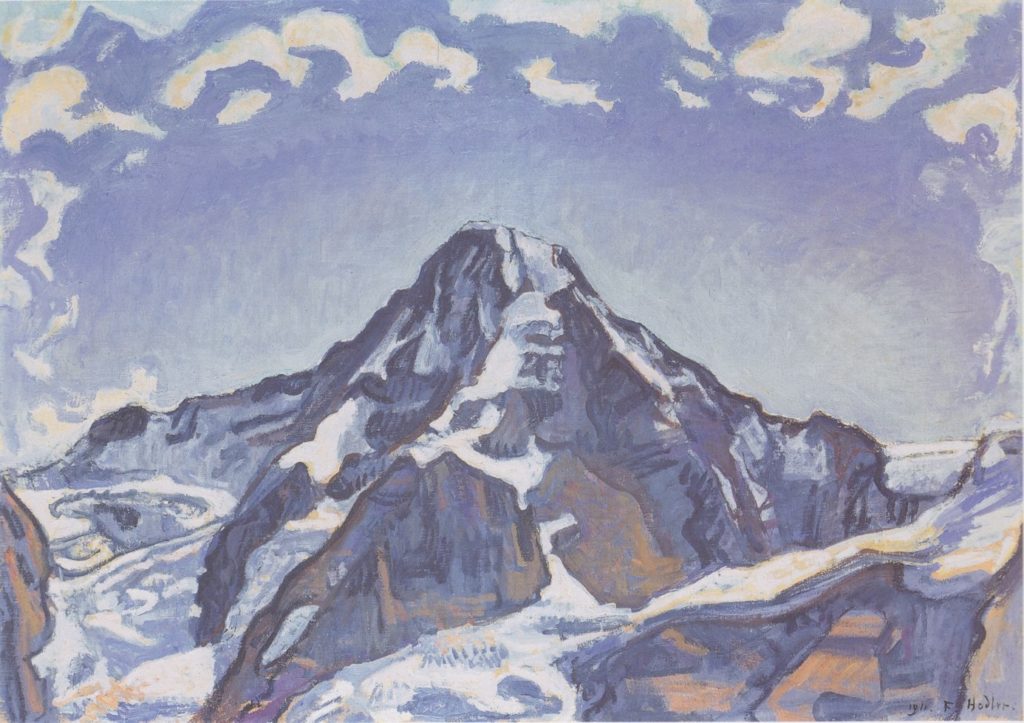

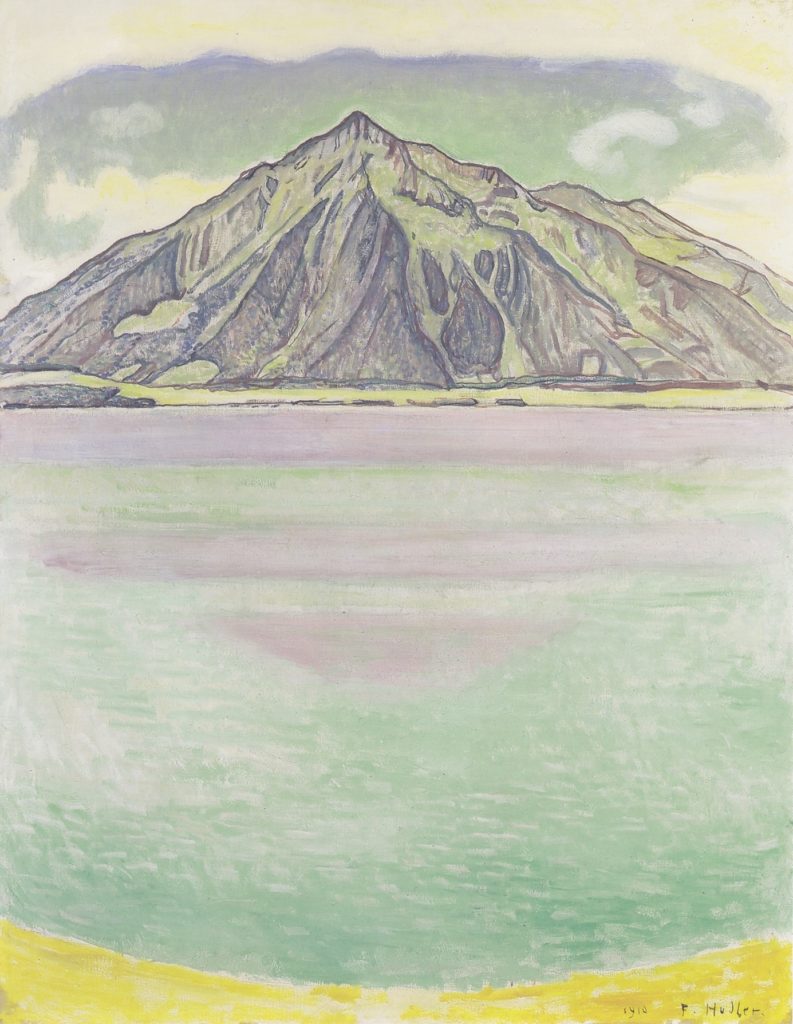

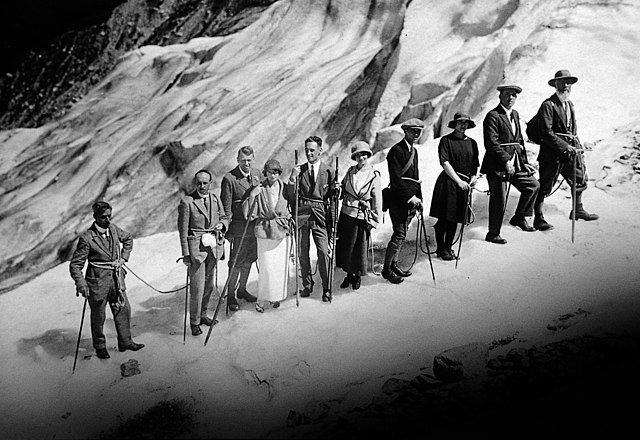

Mountain portrait

Hodler also innovated mountain painting by proposing new paintings: by tightening the composition, he no longer proposed a panorama, but instead concentrated attention on a single mountain. Hodler then painted true mountain portraits. It is therefore revealing to compare these paintings with some of the painter's portraits, but also with some of his self-portraits. But it is also interesting to make the connection between this new type of composition and the ever increasing development of mountaineering, since the latter also focuses on one particular mountain at a time. It is not uncommon forHodler to choose portrait rather than landscape format for these paintings.

The BerneseOberland and the Niesen

Although he soon moved to Geneva, Hodler always remained attached to his native Oberland . He painted the shores of Lake Thun on numerous occasions, concentrating particularly on two mountains: the Stockhorn and the Niesen, two summits mountains that had been popular and climbed since the Renaissance. The Niesen, a mountain with an almost perfect pyramid shape, could not help but leave its mark on Hodler, who depicted it on numerous occasions.

In fact, Hodler often paints the same subjects in different moods. However, this has nothing to do with impressionism: Hodler is interested in symbolism and not in the transcription of the atmosphere, the light conditions etc. specific to one or more given moments.

Geneva and the Mont Blanc

Hodler spent the last years of his life in Geneva. Here, he repeatedly painted the Mont Blanc massif and the lake, at different times of day and in different moods. Again, these paintings can be compared to some of his portraits, even if they are of a rather special kind: portraits of his wife, painted when she was dying and then dead. The horizontality of composition and subject can be compared in both cases.

Landscapes and experiments

Despite what this article might suggest, Hodler considered landscape to be a minor genre to which he devoted himself when he did not have a commission. Nevertheless, more than 700 landscape paintings have come down to us. It is in these paintings that Hodler experimented most often, breaking out of the shackles of classical composition.