In the heart of the 19th century, a pioneering engineer changed the course of history. Under the bold direction of Guillaume-Henri Dufour, the first 1:100,000 topographic map of Switzerland was produced. The result of a remarkable piece of work, it revolutionized the world of science, the army and administration. Here's the story behind the Dufour map, the mother of all Swiss maps.

Guillaume-Henri Dufour : Creator of the first topographic map of Switzerland

It all began when Guillaume-Henri Dufour was appointed Quartermaster General of the Swiss Army in 1832. For several years, Switzerland had been planning to complete the topographical coverage of its territory. The cantons, each on its own, struggled to acquire the most accurate plans possible. But the inaction of some is undermining the enthusiasm of others. Without a leader, the project bogged down.

Freshly promoted to his new position, Guillaume-Henri Dufour was given the task of completing the first 1:100,000 topographic map of Switzerland. To this end, he set up a topographical office in Carouge in 1838, providing frame with the resources he needed to carry out his operations. Creating the conditions for success, he surrounded himself with talented and determined collaborators. Scientists, topographers and copper engravers, all committed to accomplishing their mission.

Birth of the Dufour map : Johannes Eschmann conquers the Swiss Alps

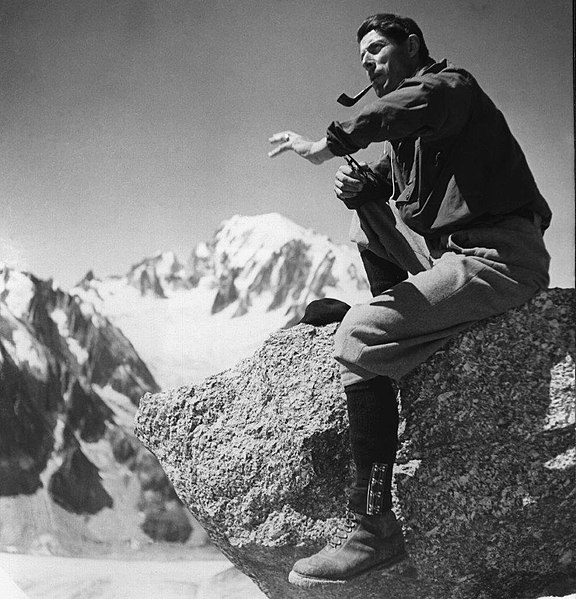

As part of his team, astronomer Johannes Eschmann carried out the essential triangulation of the Swiss landmass, a prerequisite for any topographical survey. This first network made it possible to combine cantonal data into a general plan. The team chose as reference points for their projections the Pierre du Niton, emerging from the Geneva shores of Lake Geneva, and the summit du Chasseral, in the Bernese Jura, whose altitude was then estimated at almost 1610 m. Driven by their fierce determination, the engineers had to succeed in linking all the areas of the Alps by a chain of points. Even the most inaccessible, even peaks never before climbed by man.

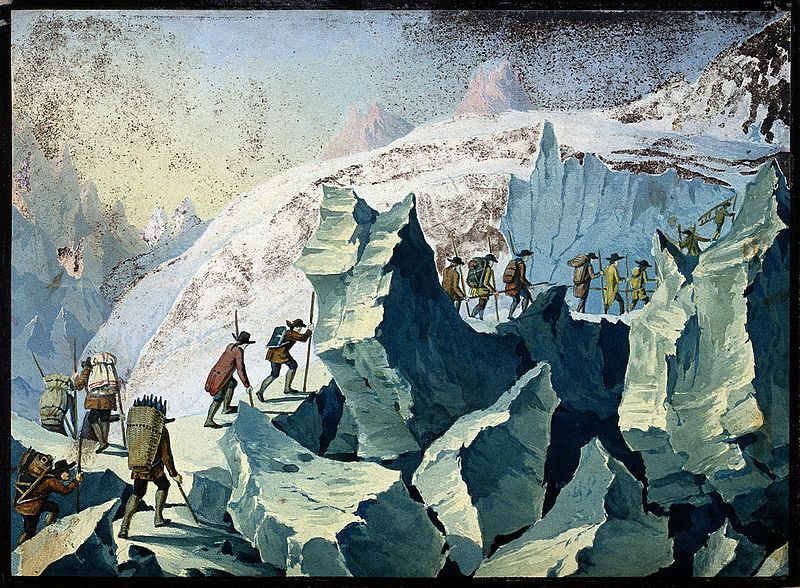

The topographers left Geneva by stagecoach to reach the heights. There were no railroads in those days! Then they had to climb and climb and climb, triumphing over snow, ice and unstable rock, taming rivers and forests. The topographers also had to contend with men, brigands and peasants who took a dim view of their crossing. True pioneers venturing into the heart of unexplored lands, they carry their measuring equipment without faltering. They are constantly on the move, trying to find the right spot to set new points.

Using a theodolite, engineers measure the angles they need to advance their business. It often takes long hours to complete these operations. In icy winds and opaque fog, it's impossible for them to make their calculations. So they camp as best they can. In the absence of huts, which would not be built by the Swiss Alpine Club until several years later, they had only their tents or alpine barns to take refuge in.

Then, once their task was accomplished, these valiant men who conquered the Alps before the mountaineers returned to Geneva. Two of these heroes lost their lives: Pierre Gobat, struck by lightning on the Säntis in 1832, and Peter Anton Glanzmann, who succumbed to a fall in the Grisons Alps in 1845. But beyond these tragedies, Dufour's team is proud to have contributed to the genesis of an exceptional map. And in 1840, Johannes Eschmann published the Results of Trigonometric Measurements in Switzerland, putting the finishing touches to the first stage of this titanic project.

History of the Dufour map : The emergence of a remarkable topographical map

On the basis of this work, engineers were preparing to shape the geodetic reference system on which the Dufour map would be based a few years later. Like a spider, Switzerland has now woven the main threads that structure its web. It now needs to tighten the links in this network to finally obtain a reliable map. These secondary triangulation operations are entrusted to cantonal topographers, while federal engineers concentrate on mountainous areas. Coordinates in hand, the canvas takes shape.

At the same time, topographic surveys began throughout the country: 1:25,000 in the Jura, Plateau and southern Ticino, and 1:50,000 in the Alps. Here too, the cantons are called upon to contribute, and many carry out the surveys on their own territory. Only the Alpine region is surveyed by the Swiss Confederation. Thus, from 1839 onwards, Isaac Christian Wolfsberger and his colleagues from the topographical office surveyed the Fribourg, Vaud, Bern and Valais Alps. In fine weather, they set off into the mountains to draw pencil sketches on plates containing between 400 and 500 points each. Then, in winter, it's time to get down to business in the topographical office. Wolfsberger, a great observer and talented draughtsman, paved the way for a new era in alpine cartography. His colleagues were inspired by his surveys, so remarkable was their clarity.

The Dufour card: A masterpiece of engineering genius

Right from the start of this enormous project, Guillaume-Henri Dufour defined the frame framework for his map. It would cover an area of 350 by 240 km, which he broke down into a precise number of areas to be surveyed. Then, as soon as they arrived at the topographical office, Dufour made a point of checking each original survey in person before handing them over to the members of his team. The drawings are then cleaned up with steel pen and converted to 1:100,000 scale.

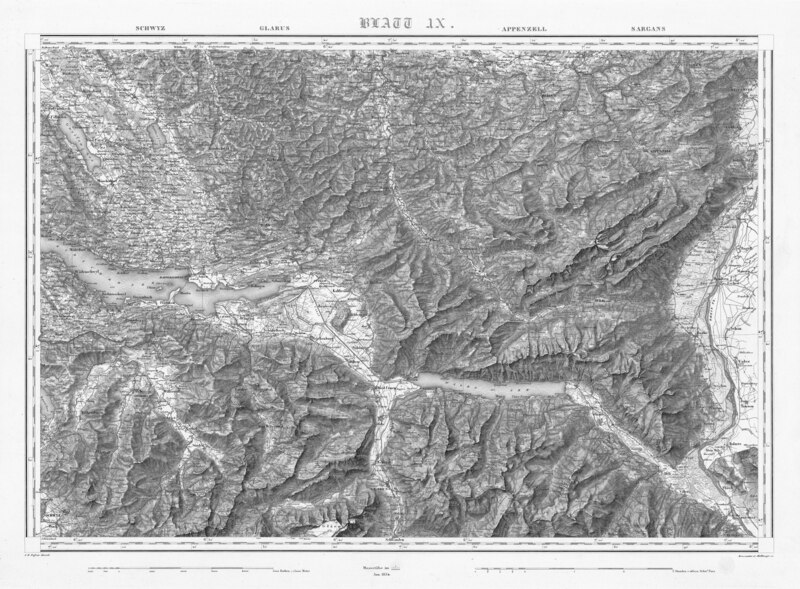

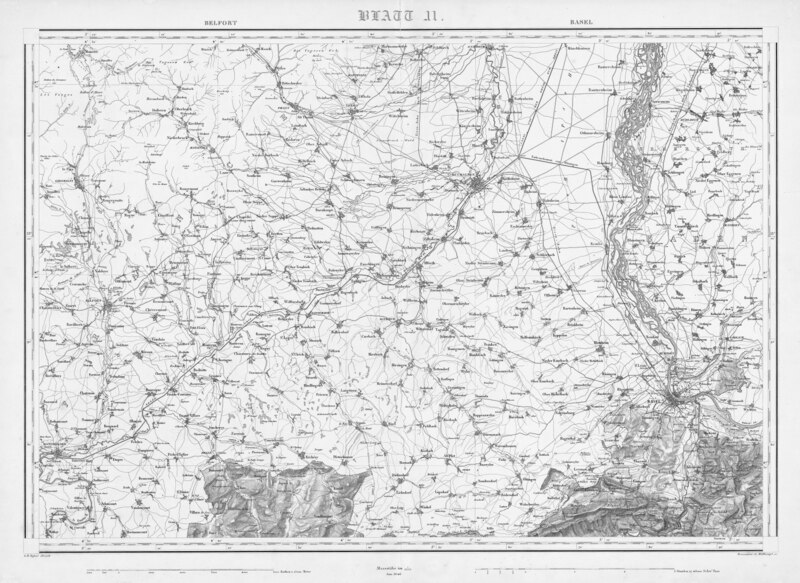

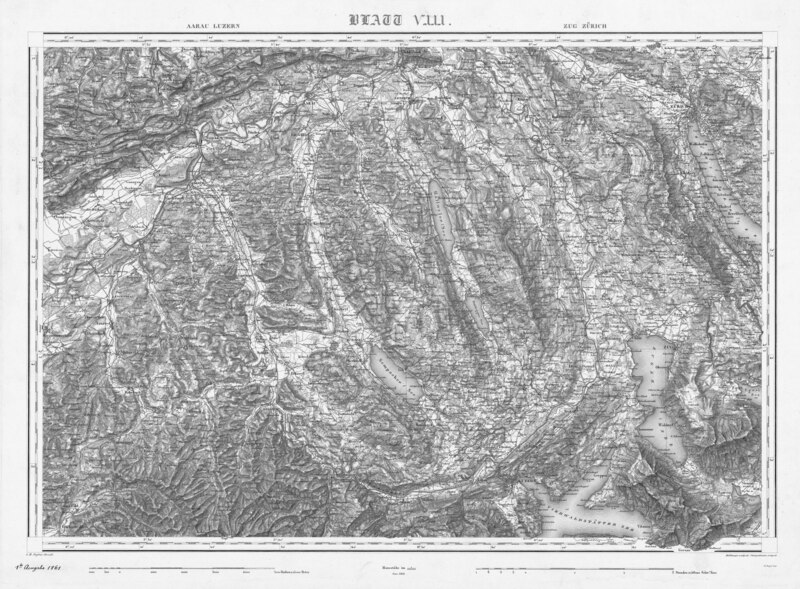

Under the guidance of renowned engravers Rinaldo Bressanini and Heinrich Müllhaupt, the plans are then engraved on copper plates. They are then printed on an intaglio press. This is where Dufour's genius and inimitable touch come into play. While many maps at the time depicted landscapes in a vertical light, leaving little room for relief, Dufour highlighted the Alps with oblique lighting. The contour lines drawn on the ground surveys fade into shadowy crosshatching. The relief suddenly seems to emerge from the three-dimensional map. This spectacular result is the finishing touch that makes Dufour's work a true masterpiece.

The Dufour map: Publication of the first topographic map of Switzerland

The first proofs of sheets XVI and XVII were published in Geneva in 1842. Each proof of the map, once reproduced, was revised and corrected before final printing. Between 1845 and 1865, almost 58,000 copies of the Topographical Map of Switzerland were finally published. As soon as it was published, the press was full of criticism. But the vast majority of the public gave the work an enthusiastic welcome. First impressions were magnificent, the relief striking. When, in 1865, all the sheets were completed, an entire hardcover atlas was devoted to them.

In 1866, Colonel Hermann Siegfried succeeded Dufour as head of the federal and topographical offices. In the years that followed, additions were made to the original map. A new work was published between 1870 and 1926. This topographical atlas of Switzerland would later become known as the Siegfried Map. To meet the needs of the army, a kilometre grid was added from 1936 onwards, and updates followed one another until 1939. Over time, copperplate engraving gave way to lithography and then offset printing. Over the years, the carte nationale was enriched with new details, but it never regained the sublime velvet of its original copperplate printing.

Guillaume-Henri Dufour: Tribute to a hero of the Swiss Confederation

Guillaume-Henri Dufour's work earned him praise in Switzerland and around the world. It propelled the country to the forefront of cartography. This first official map covering the entire country coincides with the emergence of the modern federal state. It is its first image, its highest symbol. It embodies Switzerland's national unity, relegating the differences between its cantons to the background.

The Dufour map received several international awards. In 1855, it won the gold medal for the national map at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. But the greatest reward came in 1863, when the Federal Council decided to rename the Gornerhorn after its hero. The mountain became Dufourspitze. At an altitude of 4633 m, it dominates the Swiss Alps as a tribute to the man who best represented them.

As soon as they were published, Dufour's work became an invaluable tool for the Swiss Confederation. Since then, of course, procedures have evolved, measurements have been refined and technology has revolutionized the world of cartography. But the Dufour map remains an invaluable record of the Switzerland of the time. It shows villages that have now disappeared and the retreat of numerous glaciers. Some mountains have since been renamed. Roads have been built, and the rail network developed. The Dufour map gives us a precise picture of Switzerland at the junction of the 19th and 20th centuries, revealing the major geographical, demographic, technological and cultural changes that have taken place. And if you suddenly feel like browsing through it, it is now digitized and available to the general public on the Swiss Confederation website.