From time immemorial, men have climbed mountains, fascinated by the luminous brilliance of crystals. Treasure hunters exploring the heights. Mineral lovers and thrill-seekers. Here's the story of the crystal makers at summit .

Crystal hatching in the Massif du Mont Blanc

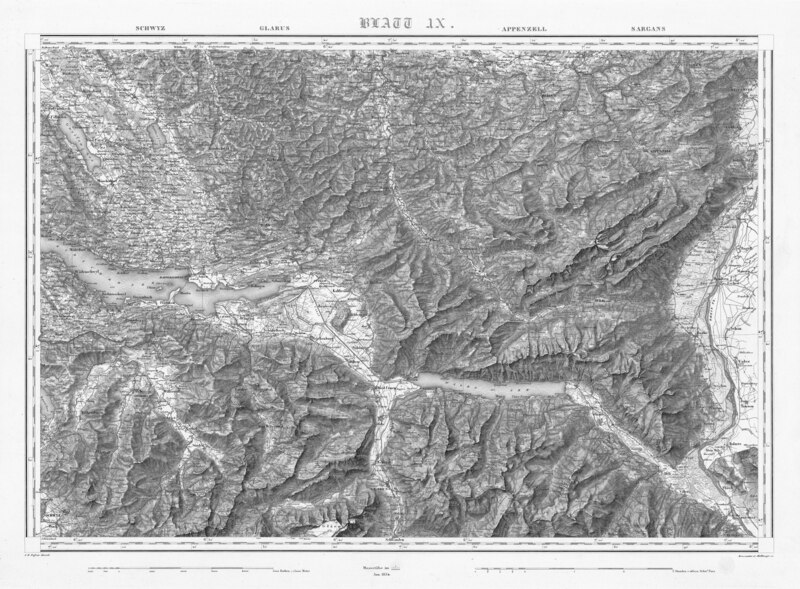

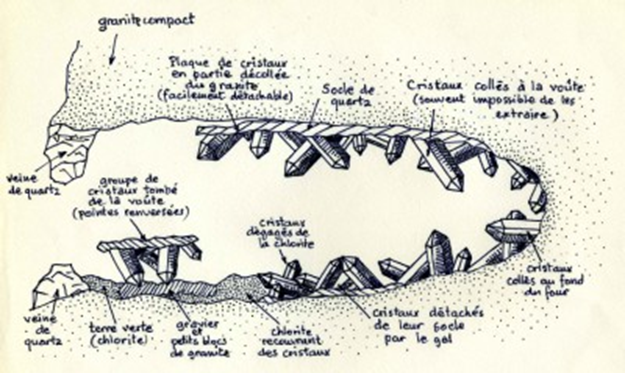

It all began 25 million years ago. The Earth shakes, the abyss boils. On the borders of Africa and Europe, tectonic plates clash and tear each other apart. During their merciless struggle, cavities form in the heart of the rock. Water seeps in, happy to escape the fury of the elements for a while. The pressure of this burning stream dissolved the silica contained in the granite. The Alps are born, Mont Blanc rises. Nature can finally breathe. On the mountain slopes, the elements calm down. The water in the hollows of its rock crystallizes. Its entrails now conceal a treasure. The crystal-lined furnaces await their discoverers.

If the Alps are rich in crystals, the Mont Blanc massif contains many of the finest. Fluorite and twisted quartz, the most sought-after by collectors, are found only in the Alps and the Polar Urals. Unearthing pink or bright red fluorite is every crystal-maker's dream. Quartz, on the other hand, can take on hues ranging from the purest transparency to the deepest black. While white quartz and hyaline quartz, or rock crystal, are ubiquitous in the Mont Blanc massif, smoky quartz and absolute black morion quartz are much rarer. And when its axis turns on itself, the crystal becomes a twisted quartz, also known as a gwindel. It is then priceless and rare, and the hunt for it becomes a Grail quest for all crystal-makers.

History of crystal makers at summit of the Alps: From prehistory to modern times

Quartz-crystal-covered geodes have been well known to man since prehistoric times. Various objects and tools cut from this crystal have been unearthed at Mesolithic sites in Savoy and the Swiss Valais. In High Antiquity, transparent quartz from the mountains was considered a precious stone, adorning ornaments and objets d'art.

Around 300 BC, Theophrastus, a disciple of Aristotle, mentions the existence of deposits in the Alps and the shaping of quartz crystals into seals in his mineralogical work Peri lithon. In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder also mentions the fame of these deposits far beyond the Alps. Echoes of their beauty endure down the centuries. From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, masterpieces made from rock crystals were highly prized by royal courts throughout Europe. Reliquaries, inlaid goblets and vases, jewels and cabochons shine with the brilliance of Alpine crystals.

This craze continued into the 17th century, when quartz, like the rare anatase, was harvested in the Mont Blanc and Oisans massifs for sale to the cutters of Paris, Geneva and Milan. Quartz trading took on unprecedented proportions, and new deposits were discovered in Savoie, notably at Doucy and Grand-Mont. The Chamonix valley became the place to be for crystal lovers. The crystal industry gradually took shape, and mineral prospecting and extraction techniques were perfected. The explorers of the 17th century paved the way for the conquerors of the Alps.

Crystal Gatherers and Mountaineering: The Conquest of the Alps Mont Blanc

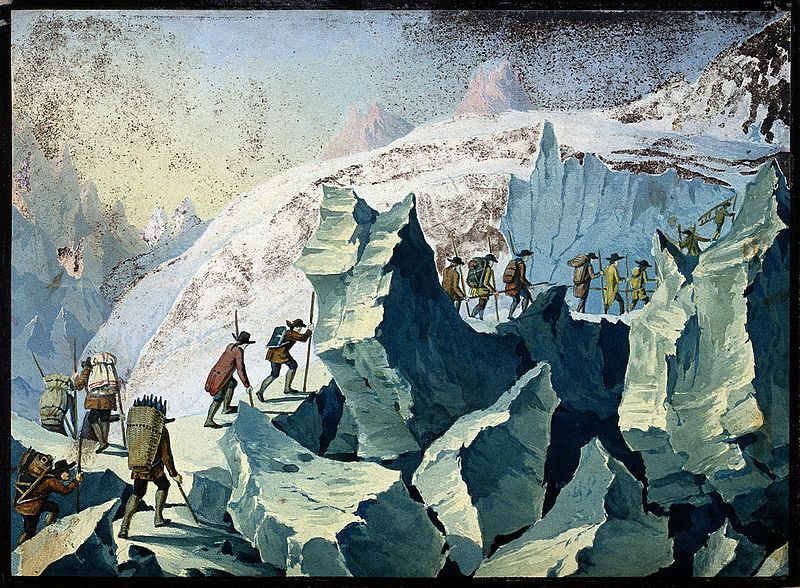

At the dawn of the 18th century, the hunt for crystals captivated men as much as it terrified them. Is it really sensible to risk your life for stones, even precious ones? It's a dangerous business, requiring stamina, caution and a thorough knowledge of the high mountains. In fact, it was thanks to the hunt for crystals that man tamed the Alps before conquering their highest peaks summits. Jacques Balmat acclimatized himself to the high mountains by collecting crystals, before becoming the first person to climb Mont Blanc, on August 8, 1786, in the company of Dr. Paccard.

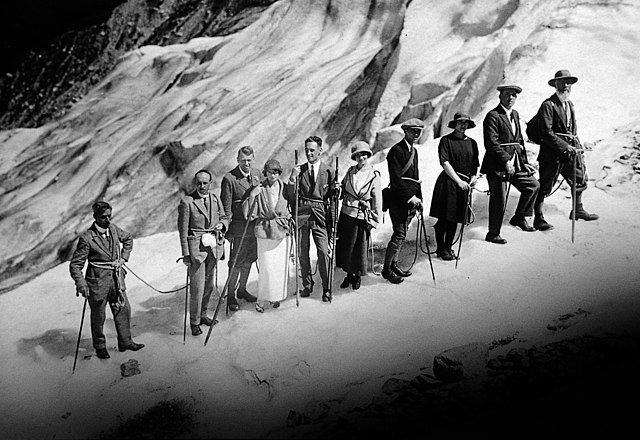

The crystal craft is also a lucrative one. And far from attracting only seasoned mountaineers, many men try their hand at the risk of losing everything to sell their finds to English tourists. Leaving their wives to work in the fields, the most destitute of them all took to the mountains with their children. Naturalism was in vogue, and to keep up with demand, the Chamonix people were ready for anything. The number of naturalist and crystal-maker mountain guides was also on the rise. The crystal frenzy is at its peak.

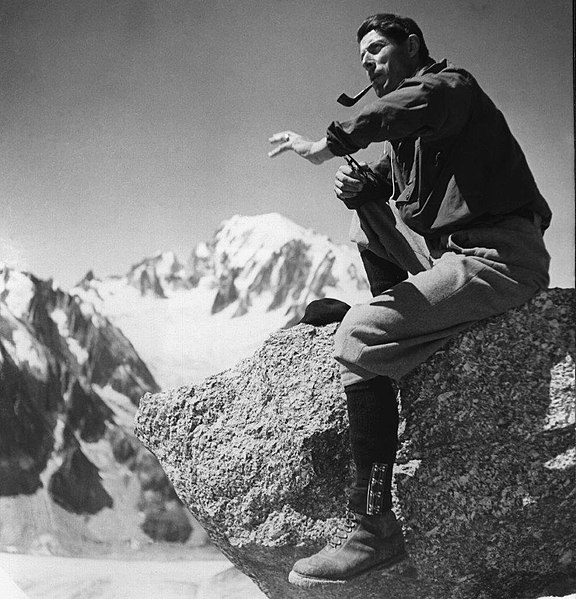

But by the 19th century, the craze had faded and crystals no longer attracted the crowds to the Mont Blanc massif. For over a century, the hidden treasures of the Alps fell into oblivion. Until a new day dawned in the valley of Chamonix. In the 1960s, young mountain guides rekindled the flame of the crystal gatherers. Roger Fournier, Jean-Paul Charlet and Armand Comte set off in search of crystals, armed with their mastery of modern mountaineering techniques. They made remarkable discoveries in previously unexplored caves. At the same time, mineralogy clubs were springing up all over the place, and mineral fairs were making their appearance. In the Mont Blanc massif, the skills of crystal-makers were passed down from father to son among the high-mountain guides who devoted their lives to summits alpins.

The crystal craft in the Alps today

Today, crystal gatherers, whether seasoned guides or passionate neophytes, pursue their dreams at the summit of the Alps. Like keen sleuths, they observe rock faces with binoculars to spot quartz veins. Then they embark on increasingly perilous traverses to unexplored crevasses. Epidote, brookite, azurite, quartz or fluorite, it's when the sun comes out that the Mont Blanc massif reveals its wonders. Then the crystal-makers set about removing the snow blocking the coveted furnace. They thaw the entrance to the cavity, scrape away the earth and clear the walls. One of them reaches into the geode to gently extract the crystals, while the other takes them in and wraps them up to protect them. Their movements are precise and their tools light, so as not to damage the collected pieces. The operation is a delicate one, as a furnace is often only a few decimeters wide and a few decimeters high.

Modern-day crystal-makers have to comply with strict regulations. A 1996 ministerial circular redefines frame their practice, prohibiting them from using explosives or helicopters to carry out their expeditions. Only traditional extraction techniques are now authorized. In 2008, the municipality of Chamonix published a decree drawn up by the town's mineralogical club. A code of honor for crystal-makers, it specifies their obligations. Every year, prospectors are required to declare their activity to the town hall and, on this occasion, formally undertake to respect this code of ethics. Then, in December, when the season comes to an end, crystal hunters must present their booty to the town hall of Chamonix, owner of the soil and subsoil of the Mont Blanc massif.

If they have made a major discovery, the crystal-makers are finally obliged to offer the town council the scoop on the sale. By acquiring the finest pieces uncovered, the town of Chamonix contributes to preserving the heritage of the French Alps. The exceptional crystals will then be added to the mineralogical collection of the Museum of Crystals. Completely refurbished in 2021 thanks to the generous bequest of Michel Jouty, a collector and shopkeeper at Chamonix, the museum now showcases almost 2,000 remarkable pieces from the Alps and beyond. Pink and red fluorite, smoky quartz, axinite, siderite and epidote are all Alpine treasures whose brilliance shines around the world.

Cristalliers at summit des Alpes: A reinvented crystal hunt

Today, more than ever, crystal makers are flocking to the region. Among the most famous are Christophe Perray, Jean-Franck Charlet and René Ghilini. But while the Alps are attracting more and more explorers, danger is always lurking. At the height of summer, the summits are dry and the rock friable. The walls threaten to collapse at any moment. In 1983, when guide Jean-Franck Charlet set off with his cousin, George Bettembourg, and two of their clients to search find crystals, he was terrified when one of them and his cousin fell to their deaths in a tragic landslide. In recent years, the disastrous consequences of climate change have further exacerbated the risks faced by crystal-makers. The gradual thawing of permafrost at high altitudes tends to weaken the rock, and rockfalls are on the increase.

Danger lurks, but does nothing to dampen the crystal-makers' fervor. The retreat of the glaciers and the irremediable melting of the eternal snows are forcing the mountains to give way. But they also reveal new territories to mankind. Untamed areas are emerging from oblivion, buried furnaces are coming to light. And the numerous discoveries of sumptuous crystals have given the bold a renewed taste for adventure. In 2003, for example, Christophe Lelièvre, janitor of the Charpoua refuge at the foot of the Drus, uncovered a furnace filled with magnificent fluorite on the slopes of the Évêque. In 2006, it was Christophe Perray's turn to make history. On the Aiguille Verte, still at Mont Blanc, he discovered an incomparable red fluorite weighing over 5 kg. He named this treasure "Laurent Fluorite" in homage to his crystal-maker friend Laurent Châtel, who had died in the mountains a few months earlier. And if you feel like it, you can admire this fabulous crystal, classified as a "cultural asset of major heritage interest", in the mineralogy gallery of the Paris Museum of Natural History.

In search of adventure, the crystal-makers never cease to criss-cross the Alps. Despite dangers and setbacks, they continue their odyssey from one summit to the next. In honor of the high mountains and sparkling nature. To sparkling crystals, its most beautiful treasures.