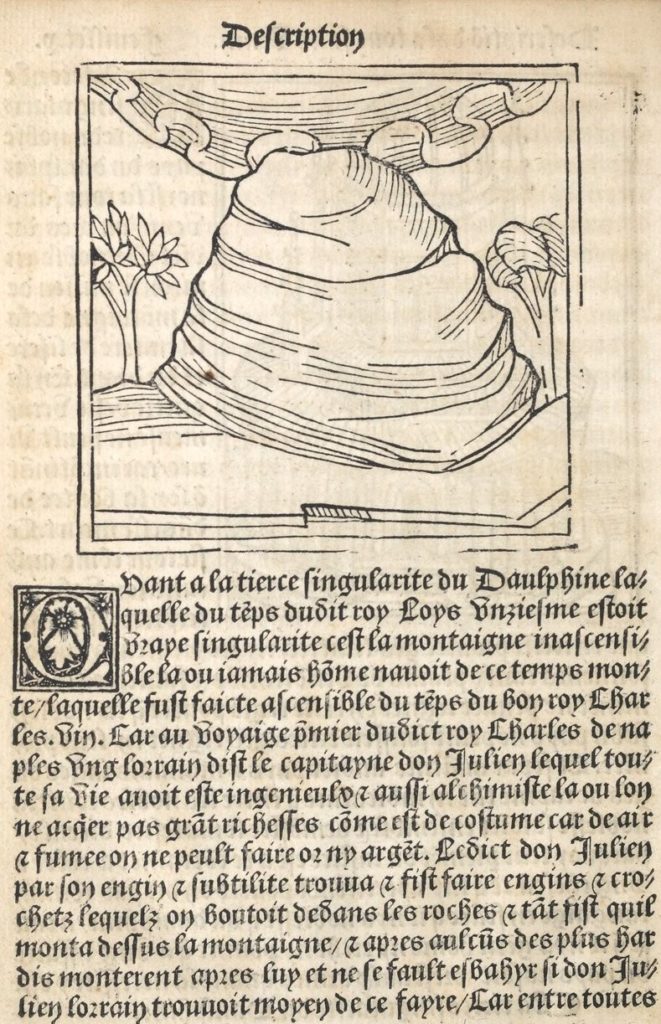

If mountains occupy a central place in many civilizations and mythologies - being for example the refuge of the gods -, it is only late that the man is interested in it. The ascent of Mont Ventoux by Petrarch on April 26, 1335 is one of the very first of its kind. It is often considered as the first awareness of the perception of the landscape and the mountain, even if the statement is a bit exaggerated. A few months before Columbus discovered America, on June 26, 1492, Antoine de Ville climbed Mount Aiguille, summit 2087m located in the Vercors, on the orders of King Charles VIII of France. The summit was surrounded by legends, but especially reputedly inaccessible. The ascent, result of a long prepared expedition, will cause a great craze. The second ascent of Mount Aiguille was only made in 1834.

Swiss humanists of the 16th century were fascinated by the mountains

The mountain craze really took off in 16th-century Switzerland, among a circle of humanists, at a time when global warming had been bringing a more Soft climate to Europe since around 1450. Conrad Gessner (1516-1565), one of these humanists and author of a Lettre sur l'admiration de la montagne (Letter on the admiration of mountains), considered mountains to be a particularly privileged and special environment:

"Here, in a deep and religious silence, from the top of the sublime mountain ridges, one could almost perceive the harmony, if there is one, of the celestial spheres."

Conrad Gessner (1516-1565)

He even "declares anyone who does not consider high mountains very worthy of long contemplation to be an enemy of nature. Surely the upper parts of the highest peaks seem to be above ordinary conditions and escape our weather, as if they were part of another world."

Some ascents in the 16th century

Martel, a friend of Gessner's, found the inscription Love for the mountain is the best (in Greek) at summit . It was still there in 1666, as testified by Muralt, one of the first glaciologists, who himself came to summit . The abundance of similar inscriptions suggests that climbing the Niesen, if not other mountains, was a common practice as early as the second half of the 16th century.

Pilate was climbed three times, in 1518, 1555 and 1585. Legend has it that the tormented spirit of Pilatus came to take refuge in a small lake located on the heights of the mountain (the lake has now disappeared) and that it triggered storms and tempests if disturbed. The Lucerne government therefore forbade the climbing of Pilatus. However, in order to test this popular belief, ascents were undertaken in 1518, 1555 and 1585, with the permission of the city. The first attempt did not reach the lake and it was not until 1555 that Conrad Gessner was able to testify that nothing happened if a stone was thrown into the lake. It was not until the new ascent in 1585 that the city of Lucerne lifted the ban.

Sebastian Münster

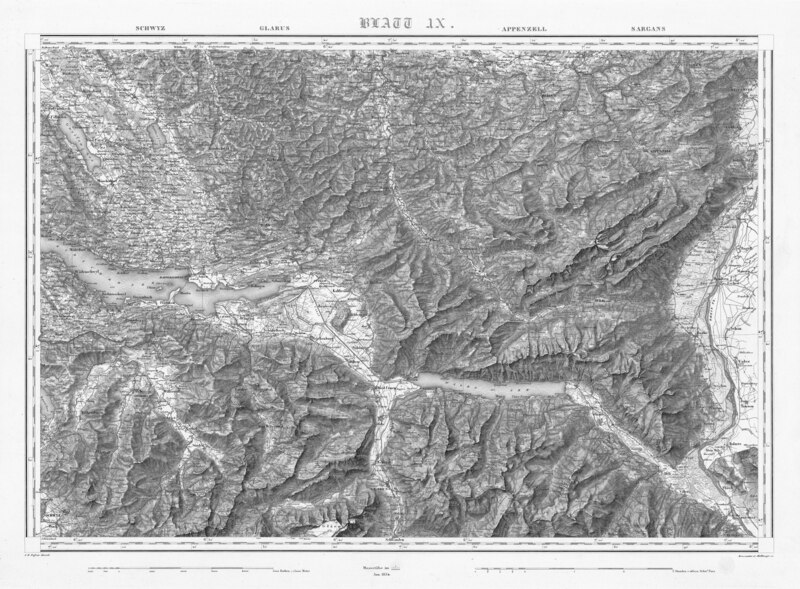

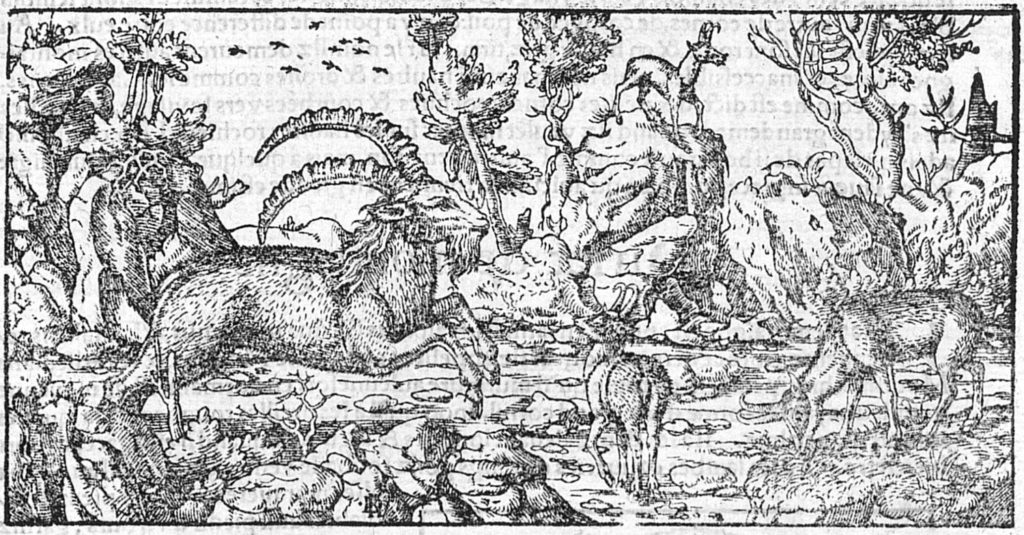

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552), humanist and cartographer, is another important figure in the discovery of the mountains in Switzerland in the 16th century. He wrote about them in his Cosmographie universelle, a work rich in geographical details and data. The illustrations are the earliest images related to travel in the Alps. The scholar lingers on describing the alpine animals, in particular the ibexes, marmots and grouse, of which the Cosmographie, by several plates, proposes illustrations of which the concern of detail and precision is obvious. The engraver shows however his limits and that he is borrowed to make these animals present only in mountain, in the first rank of which the marmot, because that does not correspond to his visual equipment. The chamois have sometimes the horns in the right direction, sometimes backwards.

The Cosmography served as a travel guide, and Montaigne, for example, regretted not having a copy when he crossed the Alps to Italy. Münster, like many contemporary or later authors, dwells at length on the waters and their qualities, as well as their curative virtues according to their composition: the waters of Leukerbad, for example, are indicated for curing numerous illnesses, notably eye diseases, but also digestive problems and lack of appetite. They also promote healing and recovery from fractures.

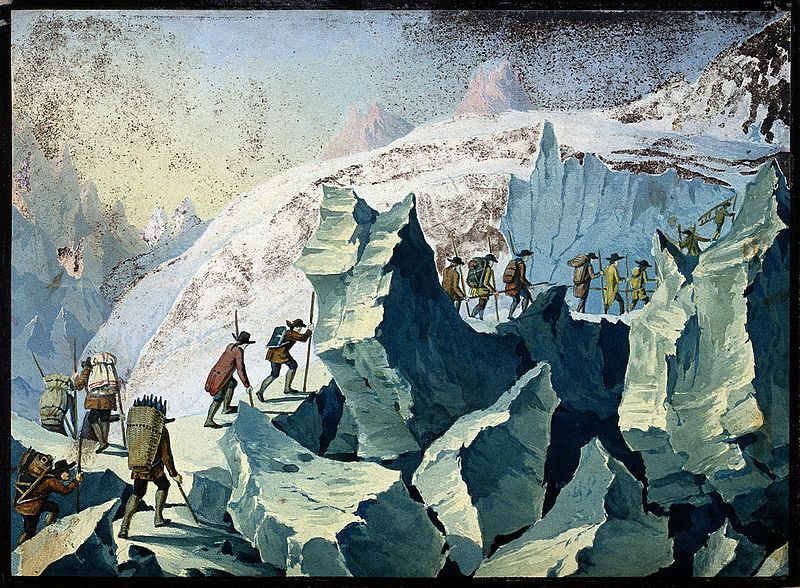

Münster was also, it seems, the first to notice the activity of glaciers - their advance and retreat - or at least he was the first to mention it. He imagines that the ice purifies and transforms into crystal, and he wants for proof the abundance of crystals discovered in the environment of the Rhone glacier. Münster also reports on the first explorations and scientific measurements on the glaciers.

Aegidis Tschudi, father of Swiss history

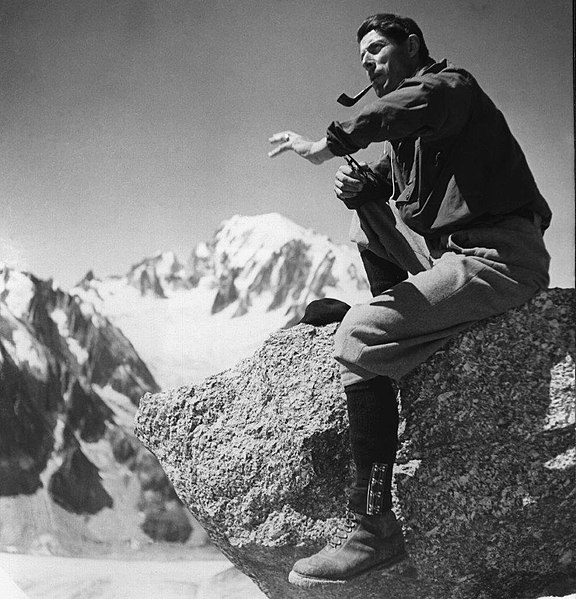

Aegidius Tschudi (1505-1572) was a major player in the history of the perception of the Swiss Alps in the 16th century and their discovery. He made two trips to the Alps, the first in the summer of 1524.

This journey is poorly documented and it is difficult to get a precise idea of it. But it led Tschudi from the Great St. Bernard to the St. Gotthard massif, passing through the Aosta Valley and the Valais; in the Gotthard, he was interested in the sources of the Rhine, the Ticino, the Rhone, the Aare and the Reuss. Tschudi considered this region to be the highest in Switzerland, an error later repeated by many intellectuals until the 18th century. From the Gotthard, Tschudi went on to the San Bernardino and the surrounding mountains in the present-day canton of Graubünden, and finally to Splügen.

Tschudi was not content to stay on the paths during this trip, going instead to the glaciers, notably the Theodulgletscher, at an altitude of nearly 3300 meters, which makes it the highlight of this trip. Tschudi's concern for testimony and vision is obvious, as he frequently adds in his vidi notes, a means of attesting that he has indeed seen with his own eyes what he is talking about.

Based on these two journeys, Tschudi published the book Alpisch Rhetia in 1538. His contemporaries welcomed this work with interest and considered the author as a pioneer of his kind. The map published in this work contributed greatly to its success and to Tschudi's fame. This map marks an important step forward in the cartography of the Alpine arc, and thus in the awareness of this new space, even if it does not mention any summit.

Tschudi travels the Alps primarily as a historian, not as a landscape aesthete. Beat Fidel Zurlauben has called him the Herodotus or the "father of Swiss history".

And the artists?

Many artists had to cross the Alps during the Renaissance to go to Italy, the destination of choice for any artist wishing to perfect his training. Several left traces of their passage through the Alps on a sheet or a painting. This is the case of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525-1569). Carel van Mander, biographer of the painters of the old Netherlands, even wrote that "he had swallowed the mountains and rocks in order to vomit them on his return".

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), a German painter, also crossed the Alps on his journey to Venice, where he painted the famous view of Arco, partially idealized. It is undeniable that the mountains have marked him. He depicts snow-covered summits in the landscape visible through a window in the self-portrait preserved in the Prado and painted in 1498, shortly after the Venetian trip. Dürer is said to have even considered producing an illustrated travel guide through the Alps.

The first real and topographically recognizable depiction of a landscape with mountains is by Konrad Witz (1400-1445/46), with The Miraculous Fishing (1444), although the main subject of the painting is a religious scene. The view is of the shores of Lake Geneva near Geneva. One can recognize different mountains in the painting: Voirons, Môle, Salève. Although the French Alps are represented in a much more schematic way, this view will mark the young Horace-Bénédict de Saussure more than three centuries later and will lead him to explore and study the Alps.

In his Treatise on Painting , Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) mentions mountains and discusses the colors to be chosen in order to paint them in the best possible way, especially to render the effects of distance. But the interest remains limited because Leonardo da Vinci only talks about mountains in their distant representation, in the background of the painting, which shows that they are not yet a subject in their own right. However, he had traveled several times to the Alps and climbed Mount Bo ( summit ), a 2,556-meter high mountain in the Pennine Alps, south of the Monte Rosa massif, where he also had a beautiful view. Leonardo would thus be the first known painter to have climbed a mountain.