The seventeenth century has a more contrasted relationship with the mountain than the sixteenth century, and sometimes more negative. This is partly due to the slight cooling of the climate at that time. Glaciers grew and sometimes swept away a church or fields in their path, causing great damage, but also making it more difficult to practice the mountain. The mountain is sometimes perceived as a divine punishment, as Horace-Bénédict de Saussure testifies:

The little people of our city [Chamonix] and of the surroundings give to the Mont Blanc and to the snow-covered mountains which surround it the name of cursed mountains; and I myself heard in my childhood to peasants that these eternal snows were the effect of a curse which the inhabitants of these mountains had attracted by their crimes.

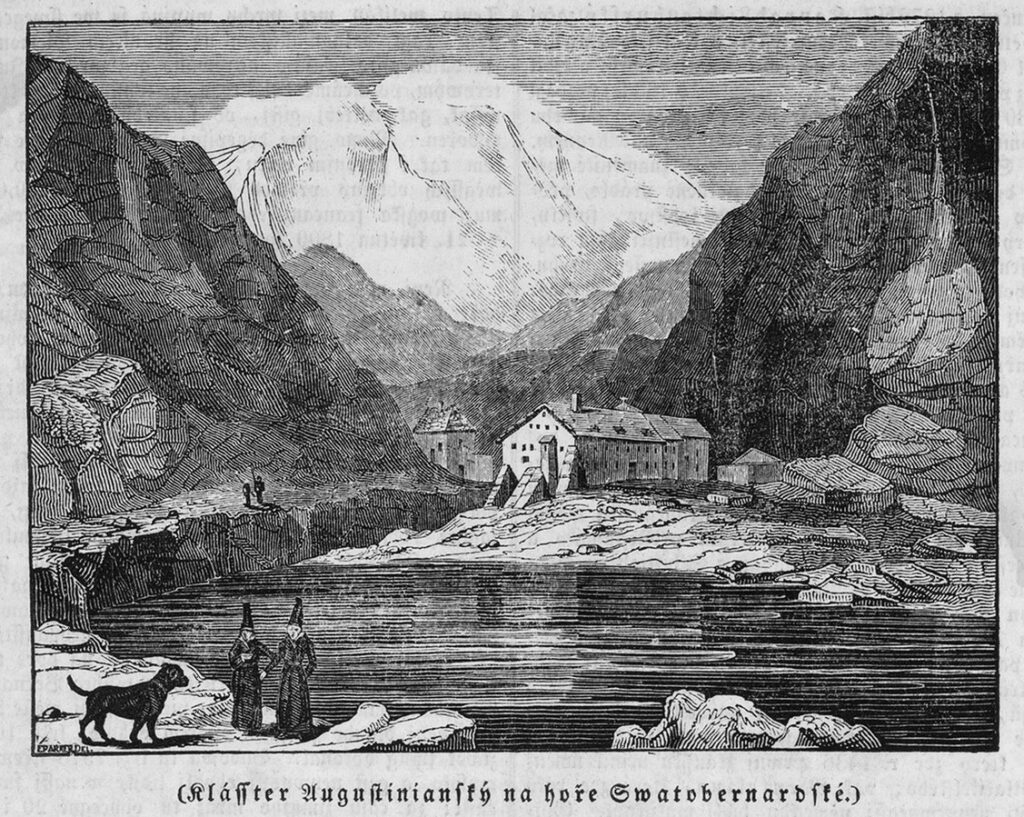

Religious processions were held to ward off fate. In the case of Chamonix, legend has it that Mont Malet - today's dent du Géant (4013m) - is the abode of a demon, sent here in exile until the end of the world by Saint Bernard de Menthon, founder of the Grand-Saint-Bernard hospice, the demon in question having previously occupied the pass of the same name. The inhabitants of Chamonix attributed the advancing glaciers to the demon, and sought protection from it through exorcism, organizing processions and imploring God to save them from this peril.

These beliefs explain why even today many mountains in the Alps have a negative name: Mount of Doom, Devil's Needles, etc.

Cursed Mountains

The mountain could even be perceived as a proof of the fall of the man and the creation after the original sin, as the English theologian and writer Thomas Burnet (1635-1715), who perceives the mountain as devoid of any utility:

Burnet thought that the earth was originally as smooth as an egg and that the mountains only appeared during the flood. The Alps are therefore for Burnet the trace of the sin that led to the flood, ruins, a pile of rubble.

Decline in the number of visitors to the Alps

Climate change in the 17th century also led to the disappearance of some mountain trails, as witnessed by Philibert-Amédée Arnod. He had wanted to cross the Mont Blanc massif via the Col du Géant in 1689, using a route that had been used in the Middle Ages. He had to abandon the Géant seracs, as Arnold recounts in his "Relation des passages de tout le circuit du Duché d'Aoste venant des provinces circonvoisines avec une sommaire description des montagnes (1691 et 1694)".

Thus, the number of visitors going to the Alps during the 17th century decreased compared to the century Previous, especially in winter, as shown by the examination of documents and archives of the period. If a revival of visitation is perceptible from 1650 onwards, it remains far from the level experienced in the Alps during the 16th century. This decrease in visitation is also due to the European political situation, for example the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). No systematic exploration and no large-scale expeditions were carried out during the 17th century.

First map of the Alps

The first representations of the Alps

However, mountains are not absent from painters' brushes or engravers' plates, and it is in the 17th century that the first representations of the Alps appear. They also appear at the beginning of the XVIIth century in engravings representing the cities, in particular by Nicolas Tassin and Melchior Tavernier, even if there is no topographic accuracy

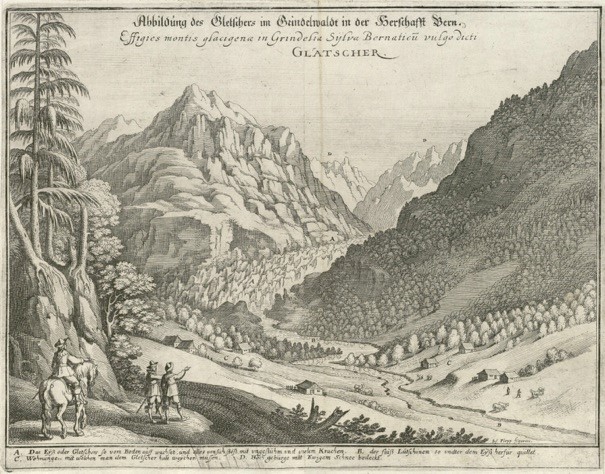

One of the first accurate representations of a glacier

The view of the glacier of Grindelwald by Joseph Plepp (1595-1642), published in Topographia Helvetiae, Rhaetiae et Valesiae by Matthäus Merian in 1642, is one of the first accurate representations of a glacier. The caption below the image refers to the glacier's advance: "The ice or glacier which emerges from the ground advances and pushes back with impetuosity and an enormous din everything that lies before it." Merian's text, whose concern for observation is evident, also shows awareness of the advancing ice:

The mountain, subject to growth, has since covered this place [the chapel dedicated to St. Petronilla]: in such a way that the local people have observed and assure that this mountain advances, pushing before it its base and land, so that the beautiful meadows and pastures that were there before have disappeared to become the wild and deserted mountain. Even, in many places, the houses and huts of the peasants had to move back because of this growth.

In the foreground on the left side of the composition are two walkers, one of whom is pointing out the landscape to his companion, and a rider, in this case a traveler. This plate is a good example of the Topographia, a work that was also conceived as a travel guide and where the illustrations frequently feature travelers, for example a rider accompanied by a guide moving on foot. Characters contemplating the landscape or, more particularly, sights are also frequent. This engraving has been reproduced in several works of the period, notably Les Délices de la Suisse by Abraham Ruchat.

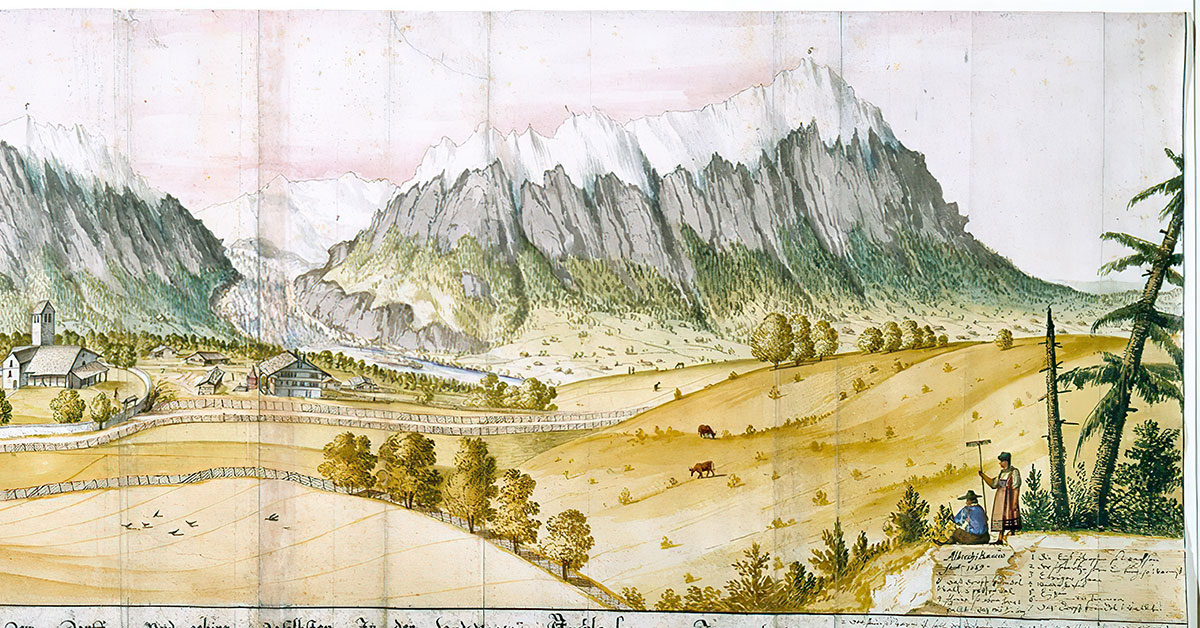

Albrecht Kauw and the panorama of Grindelwald

Albrecht Kauw (1616-1681) chose a similar but more distant viewpoint for his watercolor of 1669, more precisely Bussalp (2100m), on the heights of Grindelwald. It is the result of a journey he made on the lands of the von Erlach family and is part of a series of eighty views, all done in watercolor. Kauw's choice of locations seems to have been conditioned by Merian's Topographia Helvetiæ , which Kauw thought would complement his series. Thus, the Bernese painter did not produce any views of Aarau, Baden, Bern, Biel, Lausanne or Thun, to name only the most important places. The concern here is therefore more topographical - depicting state-owned properties - than aesthetic. This view was also intended to serve as the basis for a ceremonial painting, as a document of the period attests:

In the summer of that year [1668] a foreigner was at the country house, who painted with watercolors theEiger, the Mettenberg and the Wetterhorn, but also pictures of the church and the houses next to it. Pastor Erb said that he was going to finish a large illustration of the valley of Grindelwald, commissioned by Lord von Erlach of the castle of Spiez, that he was a painter and that his name was Albrecht Kauw.

The artist represents himself from behind drawing the landscape, a means of attesting to the veracity of the representation. The presence of a woman in the field at his side reinforces the veracity of the representation: she is a witness to the artistic process taking place before his eyes.

Felix Meyer

Félix Meyer (1653-1713) was a Swiss landscape painter. He is best known for having painted the lower glacier of Grindelwald around 1700, one of a series of thirty-two views of natural phenomena in Switzerland. The commissioner was Luigi Fernandino Marsigli of Bologna, a man who was in close contact with Johann Jakob Scheuchzer. Scheuchzer attests to the veracity of the representation, stating that the painter visited the site several times to draw it from life.

The XVIIth century has therefore, because of the climatic cooling, a contrasted relation to the mountain. Nevertheless, it was during this period that the first representations of the summits Alps appeared. We will see in the chapter Next that the XVIIIth century knows a real infatuation for the Alps.