The 18th century saw a real craze for the Alps and there was a great influx of travelers. This is due to several reasons that we will develop later, but it is the result of a slow evolution.

Dragons in the Alps

The beginning of the 18th century was still marked by popular beliefs, which were reflected in scientific research: many evoked monsters and other dragons in the mountains. Scheuchzer devotes an entire chapter of his Ouresiphoites Helveticus, sive itinera per Helvetiae alpinas regiones (published in 1723), one of the most important works on the Alps in the first half of the 18th century, to dragons. In order to write it, the scholar from Zurich accumulates testimonies of common people living in the Alpine regions, while supporting them, as far as possible, by a recognized character, in other words by an auctoritas. This chapter is embellished with several plates, illustrating different types of dragons.

It was around the middle of the century that such beliefs disappeared, thanks in particular to the progress of biology. Books that included a chapter on dragons were republished and the chapter in question was removed.

Writings at the origin of the Alps craze

This went hand in hand with a burgeoning infatuation with the Alps, especially in literature. Johann von Haller's poem Die Alpen , published in 1732, was a huge success and was published in numerous editions, spreading the taste for the Alps throughout Europe, as was Rousseau's novel La nouvelle Eloise (1761). In fact, the number of publications referring to the Alps and Switzerland increased at the beginning of the 18th century, leading to an increase in the number of visitors to Switzerland, with the number of visitors rising significantly from the 1720s onwards. This shows the close link between the appearance of Alpine literary texts and actual visits to the sites.

A recurring theme is the quality of the alpine air, which was already mentioned by Gessner in the 16th century, and which will bring many travelers to the heights, promoting the development of health tourism and the success of spas, such as Leukerbad. Rousseau even attributed moral virtues to this alpine air. It is also at this time that the topos of a Switzerland preserved from the vicissitudes of society develops: Europeans come to Switzerland to find the good wilderness.

Scientific interest

The discovery of the Alps in the 18th century also stemmed from scientific interest: the exploration of the Alps owed much to botanists - Haller was one of them - but also to geologists who were looking in the mountains for clues about the formation of the earth. There was also a growing interest in glaciers and their study. The glacier is indeed a curiosity, to the point that the mountain itself, summit, sometimes takes second place.

Johann Georg Altmann, a pastor, is the author of the first description of the glaciers of Switzerland, the Versuch Einer Historischen und Physischen Beschreibung Der helvetischen Eisbergen, published in 1751. He imagines an immense sea of ice floating on a sheet of water extending over the whole of the Alps and that "the glaciers would only constitute the flow of this one which would be released downstream from its overflow of liquid". The movements of the glaciers would thus depend directly on those of the sea. The Eisgebirge des Schweizerlandes (1770) by Gottlieb Sigmund Gruner is the first systematic work on glaciers.

A foreign world

The men of the XVIIIth century who went to discover the glaciers found themselves without references in front of this new spectacle, like the Englishman William Windham when he discovered the glacier of Faucigny:

I confess to you that I am extremely embarrassed how to give a correct idea of it, not knowing anything of all that I have yet seen which has the slightest connection with it. The descriptions that the sailors give of the seas of Greenland seem to me to approach it best. It is necessary to imagine the lake agitated by a big wind and frozen all of a sudden.

Saussure also uses this image and this is where the famous mer de Glace at Chamonix gets its name from. It is also common to associate glacial or rock formations with architectural elements, such as facades or gothic towers. The high mountain also often evokes a field of ruins.

In short, the first explorers clung to what they knew to describe this unknown world.

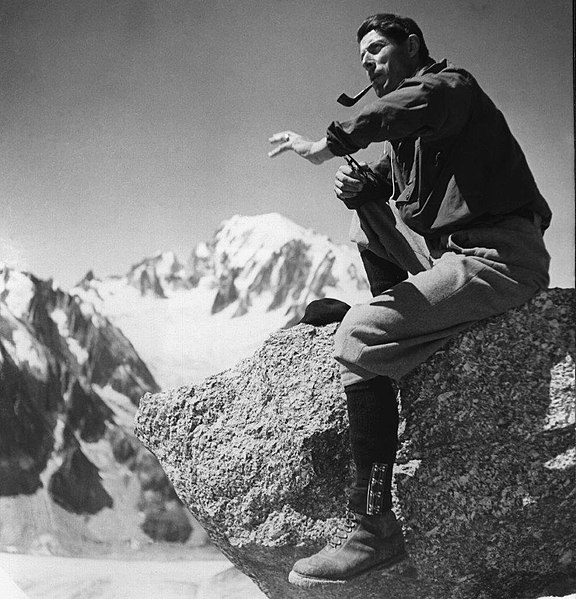

Horace Bénédict de Saussure and the Travels in the Alps

Horace Bénédict de Saussure is one of the most important scientists of the 18th century. He travelled extensively in the Alps, where he conducted numerous experiments. He recounts his experiences and wanderings in Les Voyages dans les Alpes, a 4-volume work. The book was a resounding success. Saussure inspired many other leading figures in the history of the Alps, for example John Ruskin. He is considered one of the fathers of mountaineering: he made several attempts to climb Mont Blanc in the early 1780s, before offering a reward to anyone who reached summit. This was done on August 8, 1786 by Jacques Balmat and Michel Paccard. Saussure himself climbed Mont Blanc on August 3, 1787. His writings brought many travelers to the Alps, mainly to Chamonix and Zermatt. Among these first tourists, many artists.

The English

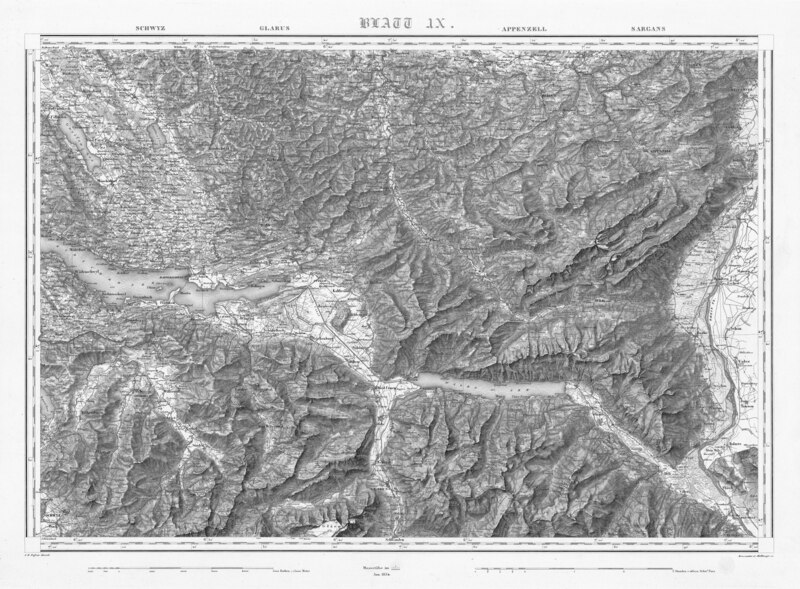

Many of these artists are English - the exploration of the Alps owes much to the English and it is moreover Englishmen, Pococke and Windham, who go for the first time on the sea of ice to Chamonix, in 1744. William Pars (1742-1782) accompanied Henry Temple, second viscount of Palmerston and member of the Society of Dilettanti, and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure on a trip to Switzerland and the Alps during the summer of 1770. Pars drew and painted the sites with pen and watercolor, becoming the first English painter to depict sites in the Valais, the BerneseOberland , central Switzerland, and the Grisons, landscapes that would quickly become classics. Pars was the first to propose an exact and reliable representation of the Rhone glacier, which he visited on July 31, 1770.

John Robert Cozens (1752-1797) traveled the Alps in 1776 on a continental journey with the art collector Richard Payne Knight, who took him to Italy. Like many of his colleagues, he worked in watercolor. The confrontation with the Alpine environment led him to break certain classical rules in the representation of landscape; thus he did not hesitate to raise the horizon, sometimes to the upper edge of the sheet. He is a very important artist in the history of the representation of the Alps, being the first English painter to represent the Alps in an artistic and topographical way. Cozens was very appreciated for the rendering of the atmosphere and for the poetic sensitivity that emanates from his watercolors. It was through Cozens' watercolors that J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851) discovered the Alps; he copied them in the 1790s for Dr. Munro.

Swiss painters

But Swiss artists were also interested in the Alps in the 18th century, such as Johann Heinrich Wüest (1741-1821), who painted them in the second half of the century. He is best known for his Rhone Glacier, now in the Kunsthaus in Zurich. The painting is vertical and the landscape occupies only one third of the composition, a pattern taken from Dutch landscape painting, which was well received in Zurich, where Wüest was active.

Johann Ludwig Aberli has a more classical approach and depicts the Alps in the distance, on the horizon, behind the city of Bern for example. The view from the city of Bern to the Alps was described by many authors as the most beautiful in the world because of the mountains on the horizon. Aberli is therefore representative of the paradigm shift that is taking place.

But the most important Swiss Alpine painter of the time was undoubtedly the Aargauian Caspar Wolf. He was probably one of the very first painters to actively travel to the Alps to paint them, even if he only limited himself to the bernese alps, Uranian and northern Valais Alps. Between 1774 and 1779, he painted almost 200 pictures, executed in the studio on the basis of studies painted on the motif. Wolf's paintings are sufficiently topographically accurate to be used as documents of the state of the glaciers at the end of the 18th century.