When rock and snow mingle with wind, the Alps shimmer and stir our souls. Contemplating this impetuous and dazzling nature, we are transported to the highest summits. A poetic journey or a quest for initiation, the peaks guide us from shadow to light, as if into the heart of ourselves. And when man photographs the mountain in black and white, it becomes a masterpiece, an eternal diamond.

Black and white mountain photography: A complex art form

Until the 19th century, the high mountains remained a frightening, unexplored land. Then came the time of the first ascents. The vertiginous feats of mountaineers played an essential role in bringing the summits the Alps to light. But their beauty is only revealed to the public in dreams, and only the adventurous then have the chance to admire the details of their peaks. Of course, the art of drawing allows the world to discover Alpine panoramas. But drawing mountains requires long days of observation, conditioned by the sometimes rapid evolution of the weather. Could the fame of the mountains find its salvation in photography? Many still doubt it.

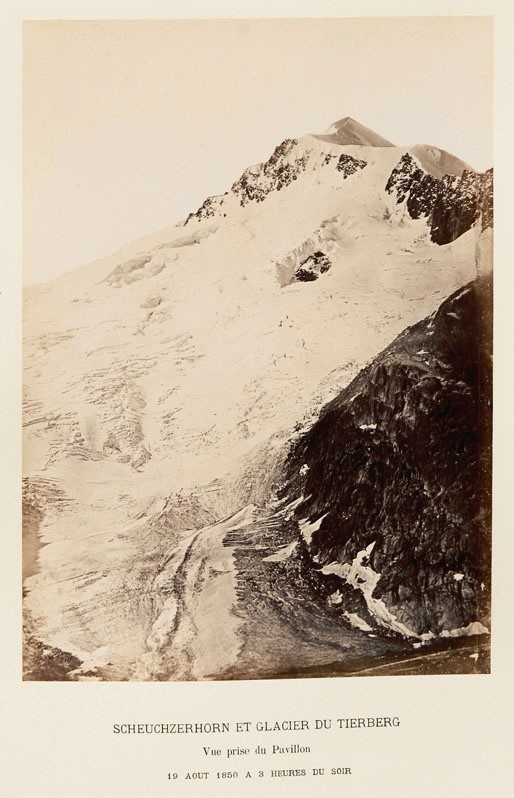

But when photographer Camille Bernabé saw his first shots of the Scheuchzerhorn on August 19, 1850, he couldn't believe his eyes: "The Alps can be photographed! The photographer as ambassador for an inaccessible and disproportionate nature: despite the obstacles, the idea made its way into the minds of mountaineers, scientists and artists.

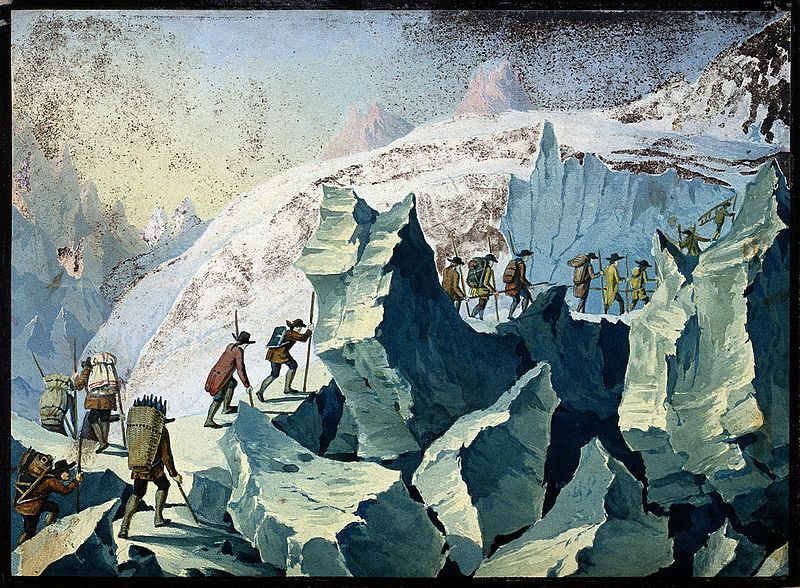

The main constraint on early mountain photographers was the considerable weight of their equipment. Imagine the titanic efforts that men and mules had to make to transport such heavy and cumbersome equipment into the mountains! In the 1850s, in the age of wet collodion glass plates, photographer Auguste Rosalie Bisson was obliged to take nearly 250 kg of fragile and expensive equipment with him on his expeditions. The experiment bordered on the impossible. And if the sun suddenly gives way to a thunderstorm, the operation can quickly turn deadly.

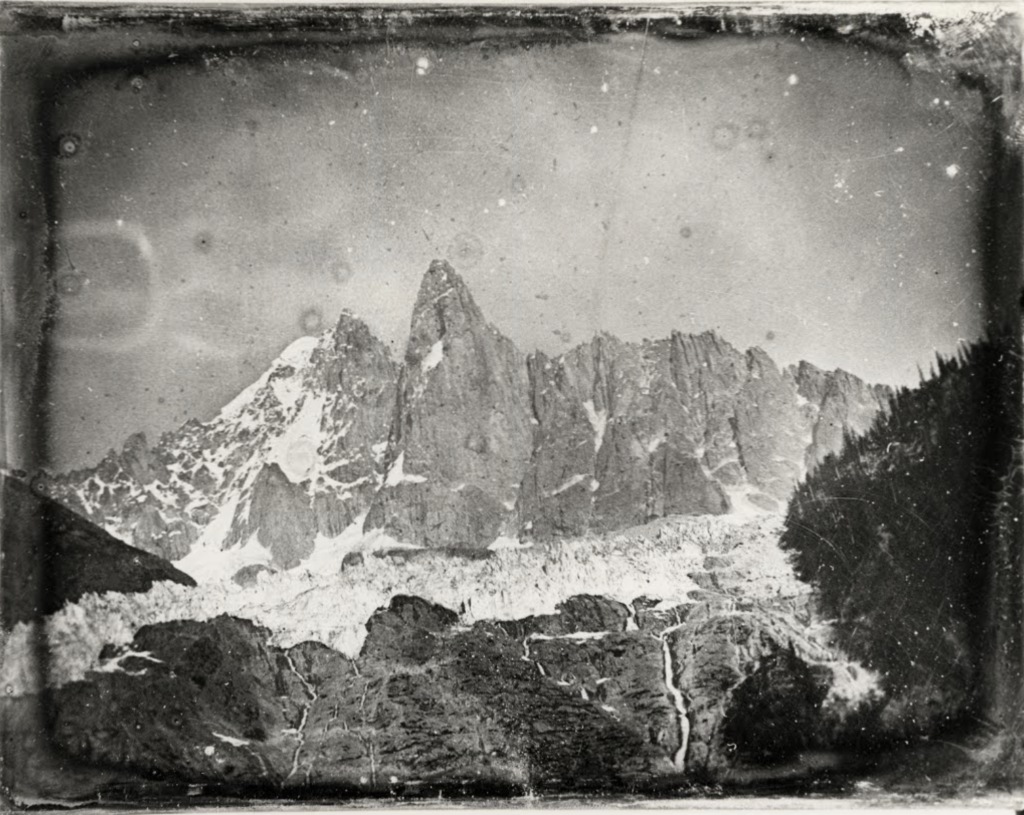

Nor does the complexity of photographic processes make them easy to use outdoors. Producing a daguerreotype requires highly specialized knowledge. As for the first negatives, they had to be developed on site, forcing photographers to set up a makeshift darkroom on the mountainside. The low sensitivity of photographic plates also made them difficult to use outdoors. The long exposure times required to capture the images can prove problematic when the weather turns. Immortalizing a panorama in these extreme conditions is no mean feat. In 1866, Aimé Civiale worked for 5 hours to create a 360° panorama of the Bella Tola heights. The 14 views then assembled each required between 12 and 15 minutes of exposure. Added to this serious difficulty was the glare caused by the snow, which often forced photographers to work at dawn or dusk.

But, far from putting them down, hardships encourage men to surpass themselves. On August 8, 1849, John Ruskin, stationed in Zermatt, made history by taking the very first daguerreotype of the Matterhorn. Black-and-white mountain photography saw its first successes. As photographers moved from the valleys to the peaks, they stopped at nothing. In 1861, Joseph Tairraz and the Bisson brothers took the first black-and-white photograph of the Alps from the summit Mont Blanc. The event received a resounding echo in society, relayed in 1862 by Théophile Gautier in the Revue photographique. Charles Soulier repeated the feat in 1869. Black and white photography eclipsed the art of painting, ushering in a new era for mountain photography.

Black and white mountain photography: a scientific and documentary challenge

Already in the 18th century, the mountain was attracting a great deal of interest from the scientific community. Horace Bénédict de Saussure, a geologist and naturalist from Geneva, climbed Mont Blanc for scientific purposes in 1787. He devoted his life to the study of Europe's mountains, particularly the Alps. His research in the fields of geology, botany, physics and glaciology contributed to a better understanding of the summits.

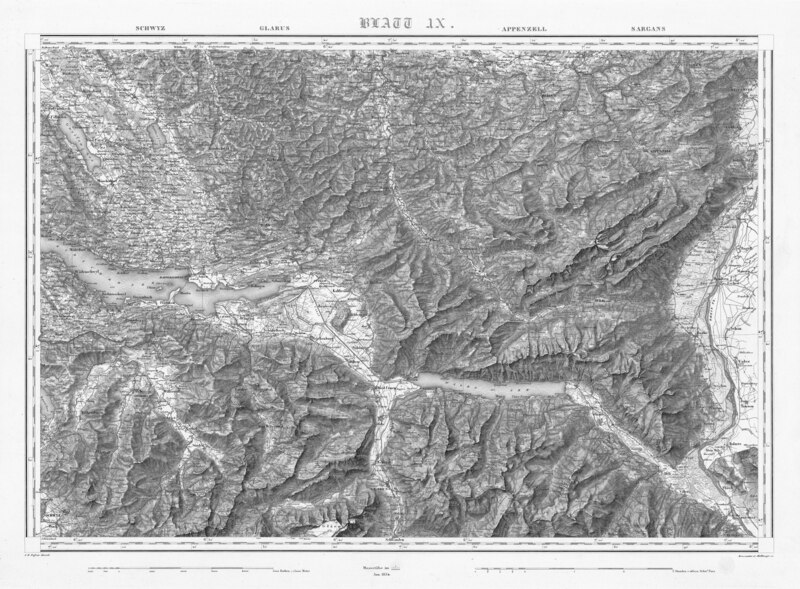

In the 19th century, the question of how mountain ranges were formed became a central part of scientific search . Geologists relied on images to support their hypotheses. From the 1850s onwards, photography was an invaluable tool in helping them to understand how the Alps came to be. Photography also played a decisive role in cartography. Aimé Civiale took almost 600 black-and-white photographs in the Alps, with the aim of carrying out a meticulous survey of their high relief.

The first mountain images aroused the enthusiasm of the scientific community, just as they fascinated the general public. This art of the real and the instantaneous offered the possibility of documenting the world and introducing the public to the splendor of distant horizons. Frédéric Martens met with great success when he exhibited his panoramic photographs of the Monte Rosa and Monte Bianco massifs in London and Paris in the early 1850s. At the same time, John Ruskin opened a new page in the history of the Alps with the first black and white photographs of the Mer de Glace, the Aiguille Verte and the Drus. The daguerreotype, officially born on January 7, 1839, provided the first illustrations of the infinite beauty of the high mountains. A priceless heritage and primordial testimony to a wild and grandiose nature once thought invincible.

Black and white mountain photography: alongside the greatest mountaineers

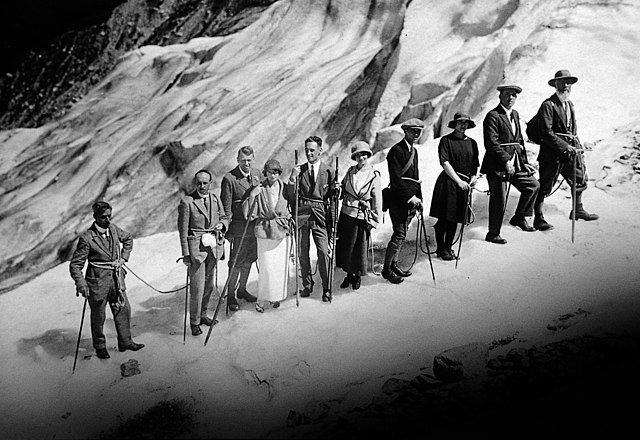

Black-and-white mountain photography really took off in the early days of mountaineering. With a single impulse, both practices conquered the sky at altitudes of over 4,000 meters. During the golden age of mountaineering, between 1854 and 1865, alpine clubs were founded, guides formed companies and first ascents were made. Photography became a major asset for mountaineers, who saw in it the possibility of illustrating their expedition stories with spectacular, never-before-seen images. As close to reality as possible, precise and expressive, photography highlights climbing routes, their tricky passages and the aspect of the terrain in a way that neither text nor drawing can.

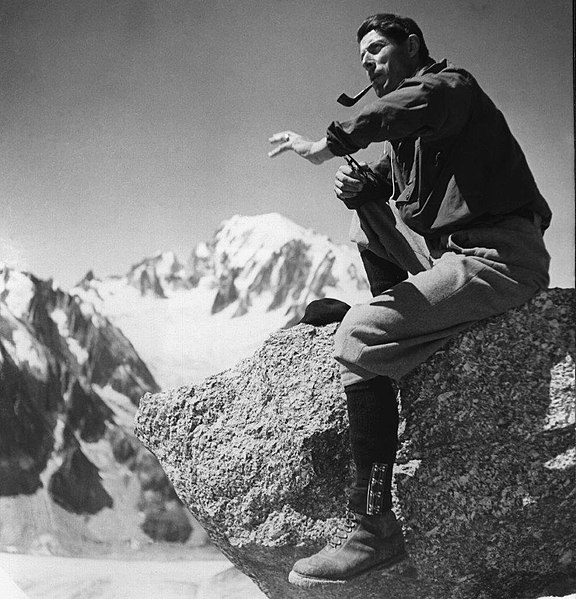

Black-and-white mountain photography also highlights the inspiring or dramatic stories of these early heroes of the peaks. Of considerable documentary interest, it comes under the heading of photojournalism. The great Edward Whymper, conqueror of the Aiguille Verte and the Matterhorn, immortalized the highlights of his expeditions to the summit the Alps. In his Carnets du vertige, published in 1956, Louis Lachenal appears grimacing with pain in a photograph taken on June 3, 1850 by Marcel Ichac during their expedition to the summit Annapurna. Shortly afterwards, the doctor amputated his frozen feet.

At last, black-and-white mountain photography was often a family affair, and dynasties of mountaineers and mountain guides were born who took a passion for this new tool. The Bisson brothers and the Gay-Couttet family are a good example, as is the Tairraz line. Joseph, Georges I, Georges II and Pierre Tairraz devoted their lives to the Alps and Mont Blanc. With their artist's eye, they succeeded in bringing out the best in the mountains. The strength of their bond with the summits shines through in their sensitive, poetic works. From father to son, they bear witness to the splendor of a majestic, implacable world. Playing with light, lines and materials, they reveal the true, heady mountain. Technique gives way to art, broadening the scope of a constantly evolving discipline.

Black and white mountain photography: An art in perpetual evolution

Over the years, photography has conquered people's hearts. Techniques evolved, equipment became more manageable and spread throughout society. In 1888, George Eastman, founder of Kodak, invented the instant camera, revolutionizing the world of photography. Compact and lightweight, Alpine lovers can easily take it with them on their ascents. Black and white mountain photography has never been so accessible.

This art form became even more popular after the Second World War, when photography switched from black and white to color. The mountain was thrust into the spotlight in 1950, when it made the front page of Paris Match. Maurice Herzog celebrated the success of his expedition to Annapurna, the first summit above 8,000 meters to have been climbed by man. As the final stage in a remarkable ascent, mountain photography became part of everyday life with the invention of digital photography and the development of increasingly affordable technologies.

Mountain photography is also diversifying its themes. In addition to scientific and documentary shots, there were also art photographs. Whereas before the 1930s, the lens only had eyes for summits , it is now gradually bringing man into the frame. And while the mountaineer's presence used to reveal the immensity of the landscape, his rope is increasingly becoming the central subject of the shots.

But beyond techniques and points of view, mountain photography never ceases to reinvent itself. Playing on the artist's gaze and the metamorphosis of an untamed, fiery nature. Digital technology offers infinite freedoms, and the mountain becomes a muse of inspiring lines. But in the face of all this modernity, what room is there for the original black and white? With its soul-splitting depth, black-and-white mountain photography is poetry. That's where it draws its strength. Revealing to the world the essential nature of the peaks, its tonalities echo the purity of snow and the rigor of rock. And whatever the photographer's objective, whether artistic search or a desire to convey, the black-and-white mountain portrait guides the viewer closer to his or her soul.

Black-and-white mountain photography, far from being the sole vestige of a forgotten era, has adapted to the world around it. For almost two centuries, it has borne witness to the history of the high mountains, its relationship with mankind and its increasingly perceptible metamorphosis.