The history between photography and the mountain goes back almost to the invention of the first:

As early as 1844, the French government commissioned two scientists, Bravais and Martens, to investigate the possibility of photographing in a hostile environment, and chose to send them to Chamonix.

And the first photographs of the Alps were daguerreotypes, and therefore unique copies.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Pranget (1804-1892) and John Ruskin (1819-1900) are in this sense pioneers and the latter boasted of having taken the first photograph of the Matterhorn (or any mountain) in August 1849.

But it also quickly met with success: the general public was fascinated by the panoramic views of the Mont-Rose massif, and then of Mont Blanc , exhibited in London and Paris respectively by Frédéric Martens in the early 1850s. Yet it wasn't obvious that mountain photography was possible, and not just for technical reasons.

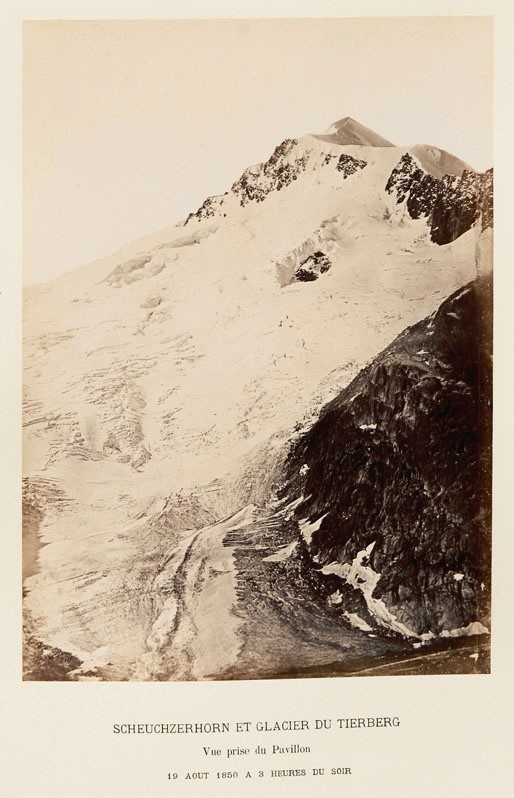

Thus, on August 19, 1850, upon seeing the first developed negatives of the Scheuchzerhorn, the photographer Camille Bernabé exclaimed, "The Alps can be photographed!"

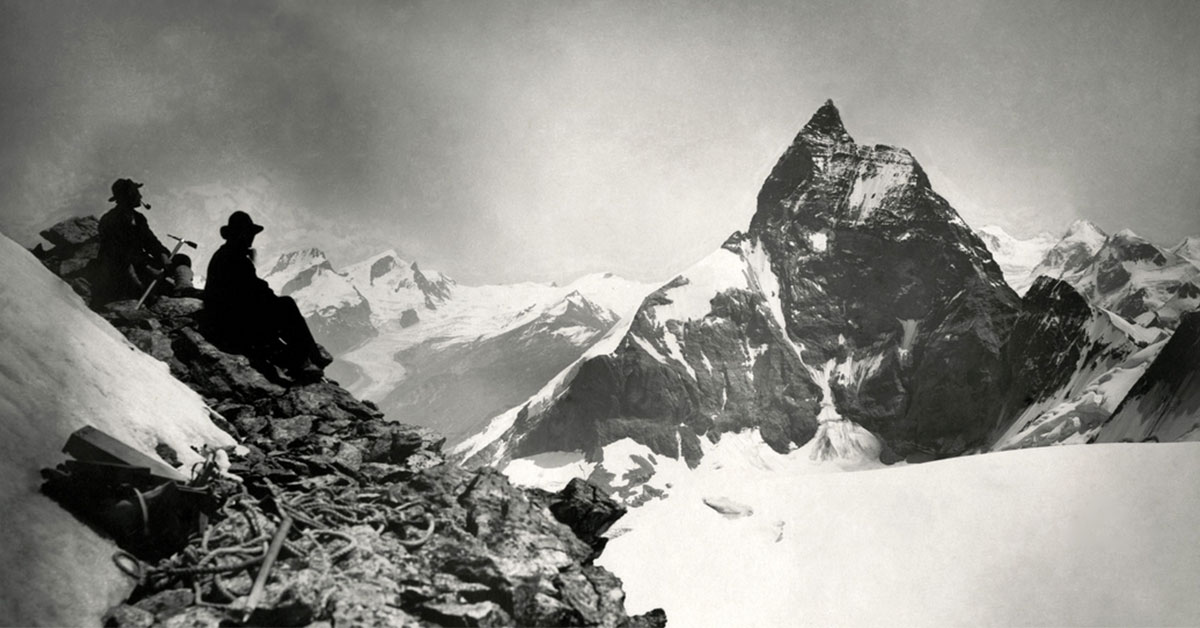

The first mountain photographers had to face many difficulties

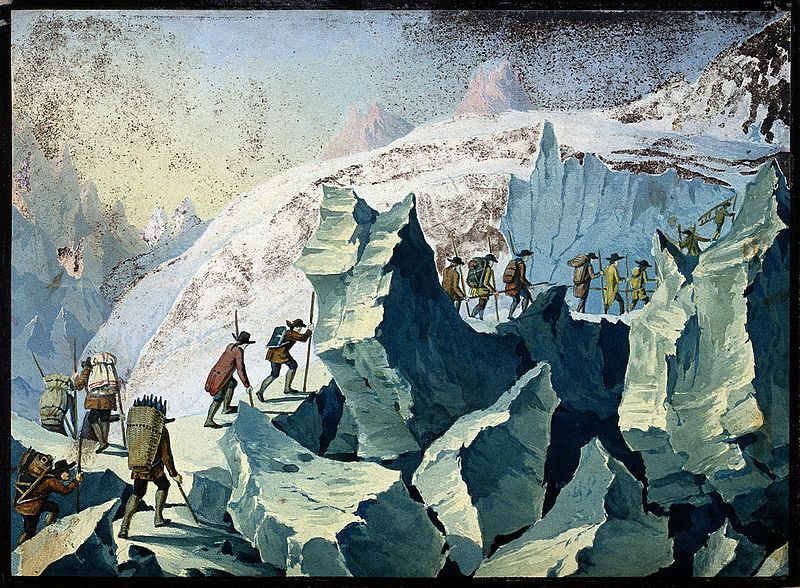

The first one is the important weight of all the necessary equipment: it takes several mules and several people to carry it in the mountains. The daguerreotype is a complex process requiring specialized knowledge.

As for the negative processes, including collodion invented in 1851, they require the negatives to be developed on site. A special tent was therefore set up as a darkroom. The first photographic processes were not very sensitive, which led to relatively long exposure times. This can be problematic in a changing environment like the mountains.

Despite these difficulties, photographers have very early photographed in the mountains, and not only from the bottom, or even at summit of the mountains, even if it is the highest summit of the Alps. In 1859, Auguste-Rosalie Bisson set out to climb Mont Blanc with the aim of taking a photograph from his summit. He did not go higher than 2800 m, but could take several photographs during the ascent

He finally succeeded in 1861 during a new attempt in the company of his brother, Louis-Auguste.

If Charles Soulier had succeeded in taking the first photograph from summit of the Mont Blanc in 1859, the success was nevertheless resounding. Théophile Gautier praised the Bisson brothers' expedition in the Revue photographique in 1862, going so far as to say that photography had succeeded where painting had failed, i.e. in representing the high mountains, the French poet writing that

"The painter's colors, if a painter climbed that high, would freeze on his palette" and that "art [...] does not climb higher than the vegetation".

This idea was widely shared at the time.

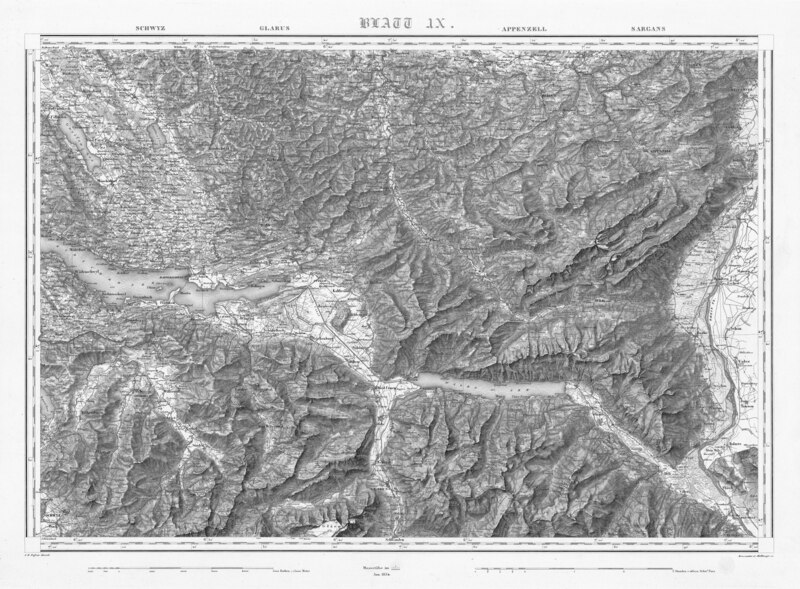

Mountain photography has played an important role in geology.

One of the biggest questions in 19th century geology was how mountain ranges were formed.

The majority of geologists of this time studied the question. And from 1830, they did so by relying heavily on images. So they naturally used photography from the 1850s.

The first mountain photographs were therefore primarily scientific and not artistic.

The Alps from the point of view of physical geography and geology - Aimé Civiale's photographic travels - is a paradigmatic example in this respect. Civiale travelled through the Alps for ten years in order to carry out an exact and meticulous survey. The result is six hundred photographs and forty-one panoramas.

The (very) low sensitivity of the plates inducing a long exposure time has another major consequence:

it greatly complicates the shooting of panoramas. With fourteen photographs, each with twelve to fifteen minutes of exposure time, and including the time needed for handling and adjustments, the panoramas are very difficult to shoot,

For example, Aimé Civiale needed about five hours in 1866 to produce a 360° panorama at summit of the Bella Tola, between 7am and noon.

The final result is thus far from being a snapshot reproducing what a spectator would see if he went to summit of the mountain in question, but the long look of a whole morning, separated into fourteen different points of view.

However, this represents a significant saving of time compared to drawing, because to produce a good panorama drawing, it was necessary to climb several times to summit - some even considered it impossible to draw an entire panorama at summit of a mountain in less than a summer, because of the difficulties inherent in drawing, but also because of the changing weather conditions.

The drawn panorama is therefore synthetic in nature: it assembles different moments of observation in a single view and allows you to see everything. The photographer, on the other hand, is dependent on the weather conditions and if the sky is overcast, some summits will not be visible on the final panorama. For this reason, some thought that photography would never replace drawing in this field.

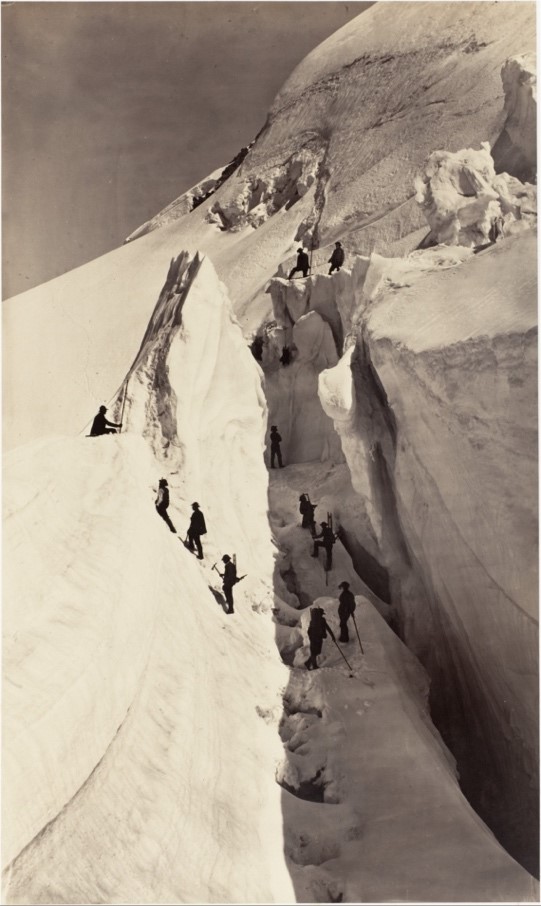

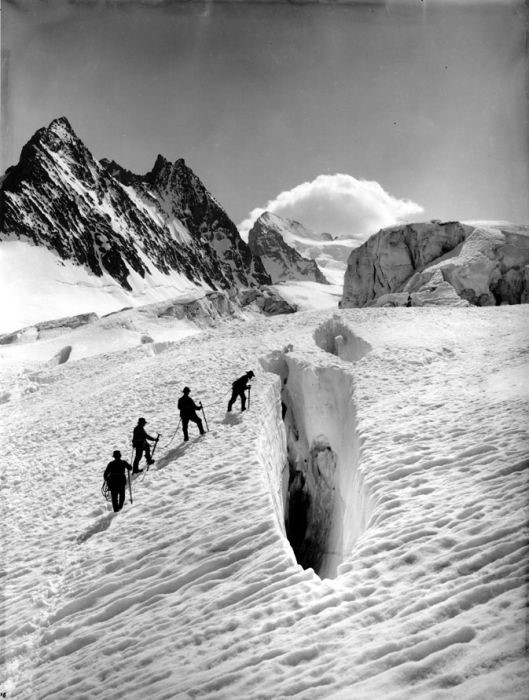

The creation of alpine clubs - the first being the English Alpine Club, in 1857 - and the development of mountaineering favored the development of alpine photography, because of the need to publish good illustrations to complement the accounts of club members. Photography is perceived as more accurate.

The ability of the camera to show everything is also a valuable asset to illustrate the routes of ascent and the most difficult passages, replacing advantageously the description and the drawing. Mountaineering and the progressive increase in the number of people climbing the mountain has led to an increase in the number of photos taken at altitude and even at high altitude.

Amateur photography underwent an important development in the 1880s

It was the invention of the instant camera and the marketing of the Kodak camera in 1888 that revolutionized mountain photography.

The latter, handy and light, is ideal for being taken "easily" to high altitudes.

Guido Rey spoke of his Kodak as "a climbing companion that you can't give up".

The 1880s were also the time of great photographers, such as Paul Helbronner, William Frederik Donkin and Vittorio Sella. The latter did not search to make scientific photographs, unlike Helbronner.

Sella was also one of the first to travel to the Himalayas.

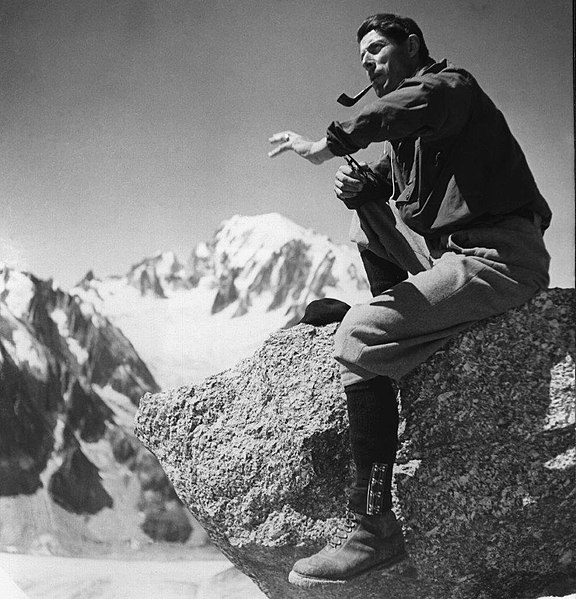

Mountain photography experienced a major turning point in the inter-war years. Until then, the protagonist of the photograph was always the mountain, even if a mountaineer was in front of the lens. More often than not, the human presence served to give scale and an idea of the immensity of the environment. By the 1930s, however, man had become the primary subject of photography, and it was more common to show the climbers' ropes than the mountains themselves.

Mountain photography experienced its true democratic diffusion after the Second World War

It is accentuated by the invention of color photography and the magazines with large print.

The publication in 1950 by Paris-Match on the front page of the photograph of Maurice Herzog raising his arms to the sky to celebrate the successful ascent of Annapurna, the first summit of more than 8000m climbed by man, is an emblematic case in this respect.

Today, it is not uncommon for a mountain photograph to occupy the wallpaper of our computers

Future articles will look at some of the pioneers of alpine photography, including:

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Pranget (1804-1892), Adolphe Braun (1812-1877), John Ruskin (1819-1900), Aimé Civiale (1821-1893), the Bisson brothers, Louis-Auguste (1814-1876) and Auguste-Rosalie (1826-1900), Gustave Dardel (1824-1899), Jules Beck (1825-1904), Charles Soulier (1840-1875), Vittorio Sella (1859-1943), Jules Jacot-Guillarmod (1868-1925).