The (high) mountain is an environment that can quickly become hostile to human presence: it is not possible to live in a world of rock and ice. The physical confrontation with the mountain also implies a physical effort and fatigue that can be disabling, especially because of the altitude. These facts have led several scientists and mountaineers to study the question, making the Alps a laboratory for experimentation. A brief, non-exhaustive overview before a second chapter, which will focus more specifically on the figure ofAngelo Mosso, an Italian doctor, physiologist and mountaineer who conducted numerous experiments in the Alps to understand mountain sickness, fatigue and loss of meaning.

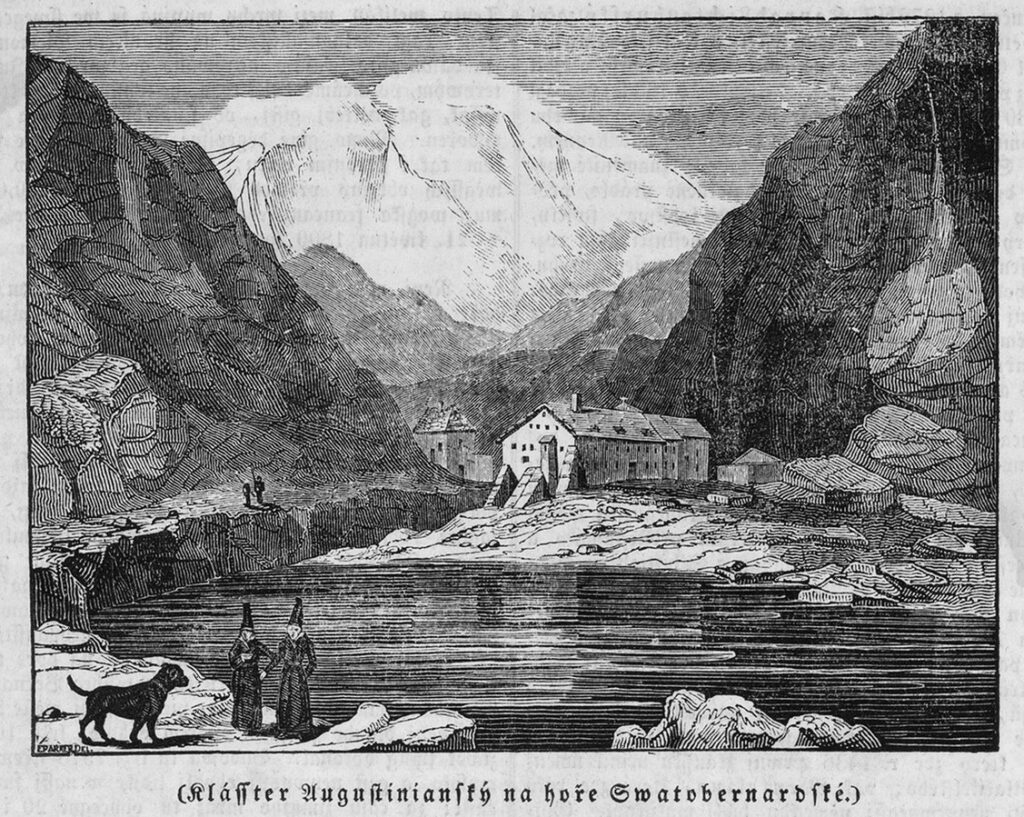

Saussure at Mont Blanc

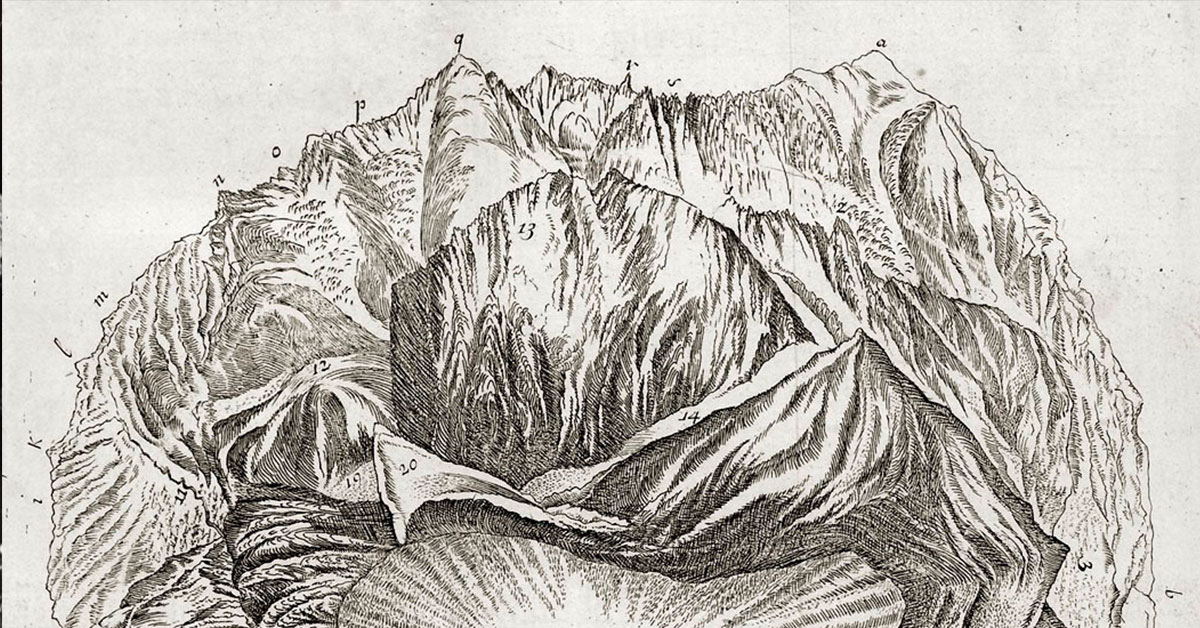

Horace Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799), author of Voyages dans les Alpes, one of the most important works on the Alps in the 18th century, was one of the first to take an interest in the effects of altitude on the human body. He assured his readers that he had taken his notes on the site itself and transcribed them within 24 hours.

When he reached summit of Mont Blanc in 1787 after several attempts, he was disappointed to find that it did not go exactly as he had expected, due to the lack of oxygen. Physical fatigue prevented him from enjoying the view he had been longing for for years: he felt like a gourmet invited to a banquet without being able to eat. The simple fact of handling his instruments caused him great fatigue, similar to that of a long walk. But this is not a failure: Saussure considered the sight of Mont Blanc a geological revelation, allowing him to understand the structure of the surrounding mountains at a glance.

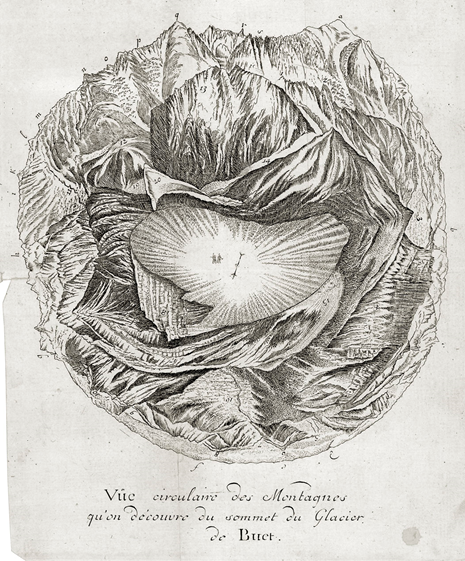

That Saussure was more concerned with himself than with the view at summit of Mont Blanc is confirmed by the fact that the presentation of a panorama seen from the summit of a mountain in the Voyages is done at Le Buet, not at Mont Blanc.

Saussure's experience at summit of Mont Blanc marks a historical turning point: the body passes from the status of an instrument of experience to that of the very object of search alpine and at the same time, the physical handicap preventing the ascent of the mountain also becomes the object of search.

When he spent 16 days at the Col du Géant in 1788, Saussure spent a large part of his time observing his body, in particular measuring his temperature, but also counting his pulses or observing the rhythm of his breathing. The purpose of his stay was however meteorological and geological observations of the mountain.

Loss of senses in the mountains

In the decades between Saussure's ascent and the Victorian climbers, the first climbers all repeat the same experience, that of the loss of sight and the loss of speech. They thus experience in pain what the theorists of the sublime had expressed earlier, that only a detached spectator can enjoy the spectacle. In the high mountains, the attempt to master the view is countered by vertigo, fatigue, drowsiness. This is what the Englishman John Auldjo said in particular after his ascent of Mont Blanc in 1827 (it was the fourteenth in history): "The mind was as exhausted as the body, I turned away indifferently from the view and, throwing myself on the snow, plunged into a deep sleep in a few seconds."

Occultation of fatigue in the 1850s and 1860s

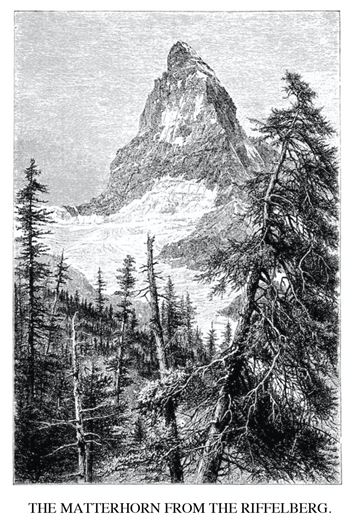

The emphasis on the loss of sight and speech begins to disappear in Alpine literature at the turn of the 1850s-1860s. The golden age of Victorian exploration of the Alps began in the mid-1850s. Climbers of this period do not talk about physical fatigue, the effects of the air on perception and speech, partly because of the need to assert a heroism that supports a proven patriotism. For example, Edward Whymper, author of many firsts in the Alps, including the first ascent of the Matterhorn, does not breathe a word about fatigue and the effect of the high mountains on the body in his voluminous Scrambles among the Alps published in 1871.

Early research on fatigue in the 19th century

But if the physical repercussions of mountaineering are evacuated from mountaineering itself, they enter fully into the field of search, of science. Since the 1850s, physicists and physiologists such as Paul Bert, Claude Bernard and their successors have been visiting libraries at search of alpine writings by amateurs, criticizing what they considered to be dubious observations. A. Le Pileur had some harsh words for these amateur physiologists, wondering how one could observe one's own body failure. The research focuses as much on mountain sickness (the expression dates back to the 1840s) as on the repercussions of altitude on the human body: breathing, heart rate, pulse, sleep, body temperature, etc. Researchers are also interested in the repercussions of altitude on perception, particularly of colors.

It is mainly continental scientists who have carried out these works and experiments on physical fatigue in the Alps, the English being more sceptical. The theme of fatigue and the research on the decrease in physical capacities also went against their athletic ideal of the mountains. There is thus a real English animosity in the Victorian era against alpine fatigue, even though English public opinion in particular expressed strong doubts about these climbs without any scientific purpose, in particular because of the risks involved. Questions were asked about the physical health of the first mountaineers, but also about their mental health, as John Murray did in his Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland, one of the most widely read tourist guides of the 19th century.

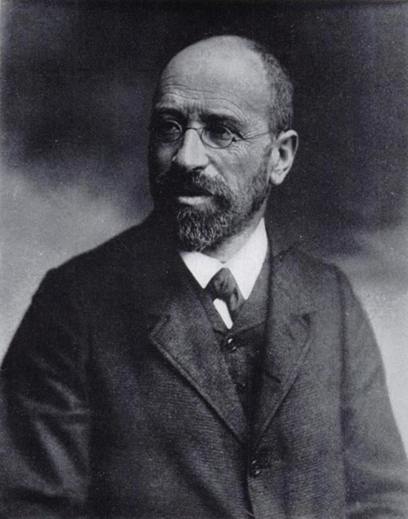

Nathan Zuntz

The German Nathan Zuntz (1847-1920) was one of the pioneers of this research on mountain fatigue. Equipped with a special apparatus, he undertook four special expeditions to Mount Rose and the Brienzer Rothorn between 1895 and 1903. He tried to determine the efficiency of the human body. He arrived at the result that one third of the food resources is transformed into mechanical work, while the rest is lost in heat. The human body would thus be more efficient than any steam engine. But it is very difficult to arrive at precise measurements in a cracked and chaotic environment. That is why Zuntz used the railway tracks of the Rothorn to obtain reliable data.

Discover the rest of this article : THE ALPS AS A LABORATORY II : ANGELO MOSSO