Angelo Mosso (1846-1910) was an Italian physician, physiologist and mountaineer. He was interested in the Alps and their impact, not physical, but physiological, on the human body. The Alps were seen as the ideal place to answer some of the burning questions of the end of the century concerning the human body, such as the reaction of the nerves to changes in the environment or the expenditure of energy and fatigue during experiments. We are therefore far from the Alps as the playground of Europe as Leslie Stephen put it. Mosso noted that the effects of fatigue are stronger in the mountains, but also last longer.

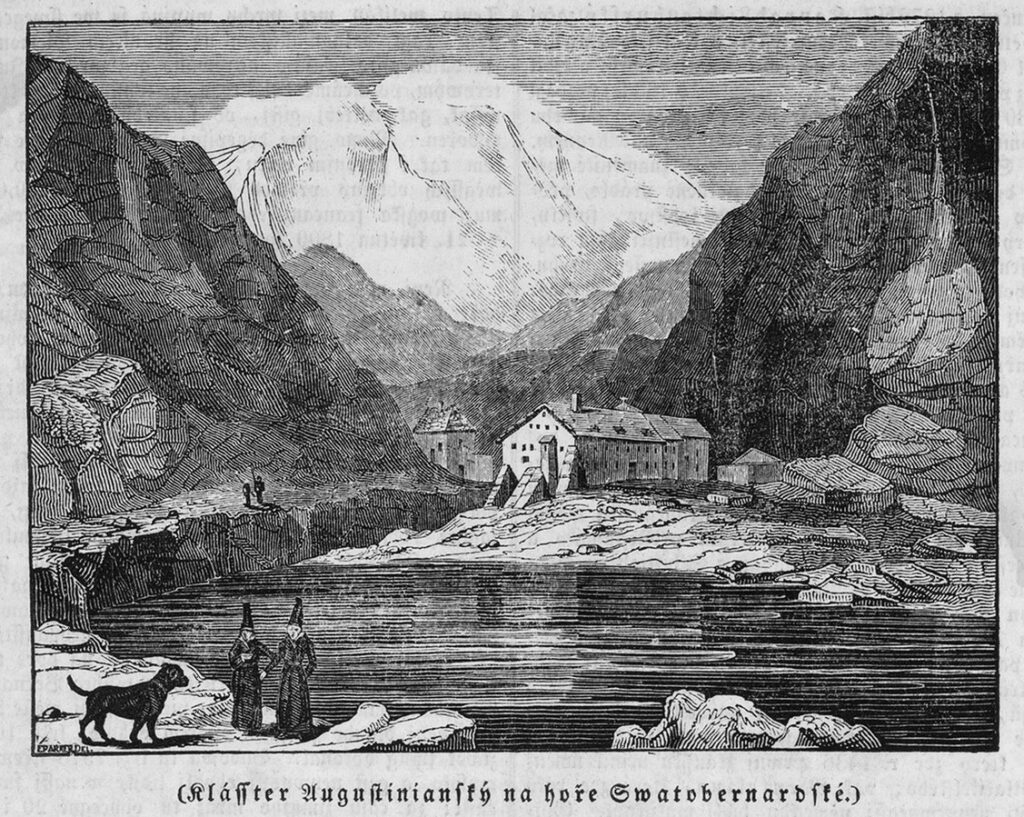

It was at the end of the 1860s that Mosso made his first observations on alpine physiology, in notebooks taken on excursions to the Alps, an environment where the only constant according to him was variety. But it was not until the 1870s that Mosso began to transfer his laboratory research to the field. Mosso took his instruments into the field, and more particularly to Monte Rosa, and reproduced in the high mountains the experiments previously carried out in the laboratory. It is thus a "laboratory escape".

Mountain sickness: body temperature in the mountains

The exact causes of altitude sickness, a term dating back to the 1840s, have occupied researchers for years. Louis Lortet, director of the Lyon Museum of Natural History, believed that the human organism could not fight against a hostile environment like the high mountains and keep its normal temperature. Observing that his body temperature had dropped several degrees during his ascent of Mont Blanc, he deduced in 1869 that mountain sickness is due to this body cooling. The Swiss physiologist François-Alphonse Forel refutes Lortet following his own experiments by affirming that on the contrary the body temperature increases, invalidating according to him the thesis of Lorteret. Mosso confirmed this result at summit of Monviso in 1878, where he measured and recorded the curves of his breathing, pulse and body temperature.

Mountain sickness: breathing

Paul Bert, in his book La Pression barométrique (1878), asserts that the origin of mountain sickness is to be found in the blood. Mosso, who was so impressed by the book that he took it with him to the Alps, took the opposite view of the Frenchman by asserting that the effects of altitude sickness were due to nerve problems, relying in particular on his research on respiration.

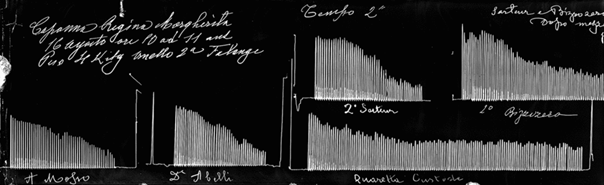

Mosso thought that the organism ingested more oxygen on the plains than it really needed, a result he confirmed in 1882 by conducting experiments (notably on sleep) and by measuring breathing at the Theodulpass, a place where there is only 2/3 of the air found on the plains. Mosso's measurements show that breathing not only does not increase, but slightly decreases, without affecting the organism. This result gave him the idea to go even higher in altitude to find the limits of this luxurious breathing. But it also led him to the conclusion that the seat of the problem of altitude sickness is to be found in the nervous system and not in the blood, contrary to what Bert had claimed. Mosso also noticed that during mountain sickness and especially if it is severe, the pauses between two breaths become longer, a phenomenon also noticed in sleepers.

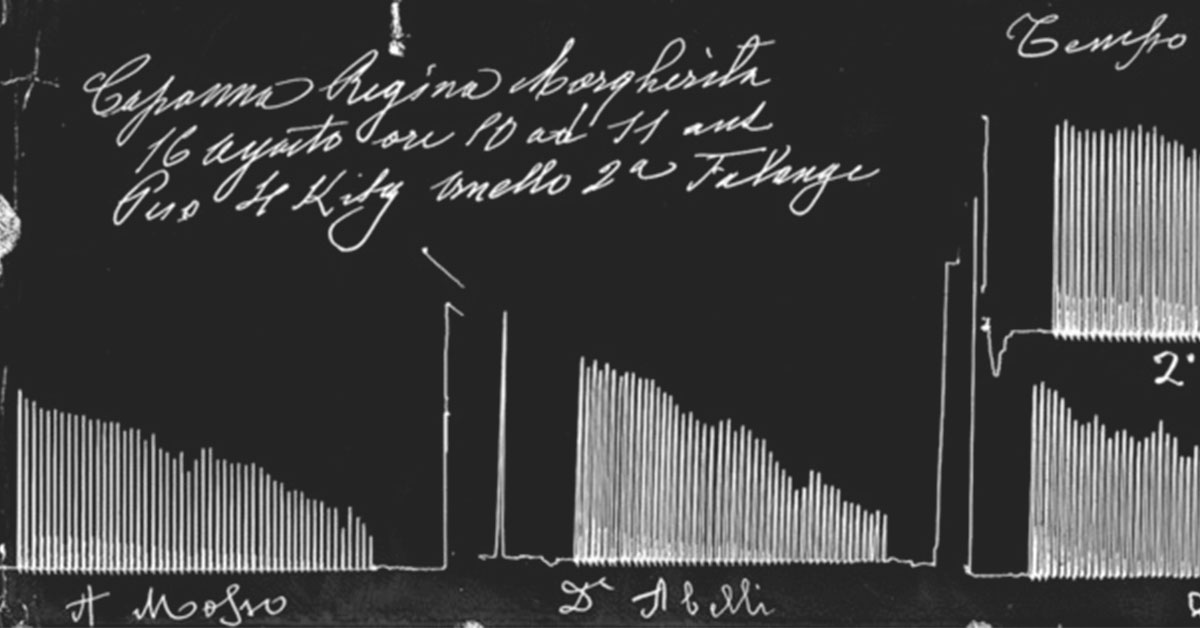

Mosso carried out extensive physiological research when he spent a month at summit of the Mont-Rose, at the Margherita hut, in 1894, a project he had in mind since the 1870s. One of the aims was to study mountain sickness. Mosso's first lines are barely legible when he arrives at the hut: he speaks of headaches, nausea, vomiting.

Over the next few days, he tries to accumulate evidence that the mountain sickness is not due to anemia and a lack of oxygen in the blood. But Mosso would later admit that he was wrong and that the altitude sickness was indeed due to a lack of oxygen, thus proving Bert right.

First winter ascent of Mont-Rose and research on colors

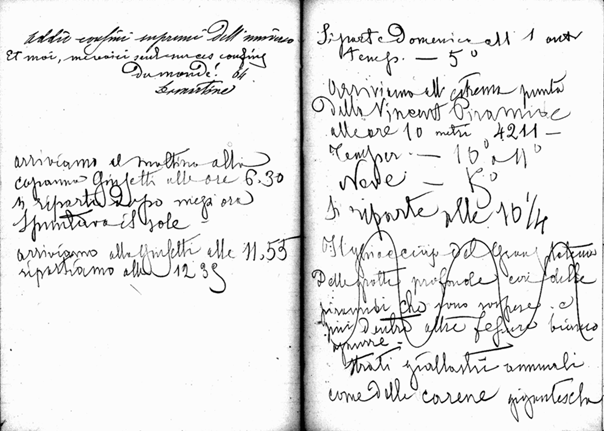

Mosso made the first winter ascent of Monte Rosa in February 1885, which he recounts in Una Ascensione d'inverno al Monte Rosa . In the last pages of his book, Mosso announces that he will soon publish another book on the effects of fatigue in the mountains. This book, La fatica, which gave him great success, was not published until 1891. Following this ascent, he copied (in French) in his notebook a verse of Lamartine: "And here I am alone on these confines of the world! At summit, Mosso notes the altitude, time and temperature. He spent 15 minutes at summit. Mosso explains that he was very tired, which explains his trembling handwriting.

Mosso justifies the winter ascent of Monte Rosa by the need to experience great fatigue, especially of the eyes. Mosso thought he could distinguish between direct fatigue caused by the glare of the sun and indirect fatigue caused by muscular work - since Goethe and his Farbenlehre , we have been interested in the limits of vision resulting from a burning sun. Mosso believed that the alpine fatigue of the eyes and muscles disturbed the perception of colors. The breakage of his mercury manometer with which he thought to measure the fatigue of the respiratory muscles prevented him from verifying his hypothesis. In spite of everything Mosso pays a very particular attention during this excursion to the colors. He wants to show that even in a world of black rocks and white snow and ice, the changing light produces unexpected effects.

Until the 1920's, the Turin physiologists and oculists took color charts to the mountains to carry out research on the modifications of the perception of colors caused by tiredness. But almost all arrived at the opposite conclusion of Mosso: the perception of the colors is reduced by the ocular tiredness.