The Alps have always inspired mankind. Fighters and poets, thinkers and novelists, they have nourished their art and reflection with the power of the mountains and their immensity. Fearsome creature or divine muse, symbol of power or solitude, the mountain becomes in turn a source of light or darkness. Awakening our most vivid emotions as well as our wildest instincts, they guide us from transcendence to contemplation, from rage to the sublime. And, at the end of the journey, brings us back to ourselves. Isn't that the ambition of every adventure? In this first instalment, I take you on a journey of discovery of the Alps in literature, from the dawn of time to the advent of Romanticism.

The Alps at the dawn of literature: a formidable stage for drama and the sacred

"We'll find a way... or we'll make one. The year was 218 BC, and Hannibal Barca was about to cross the Alps. The historian Livy recounts this military exploit in Book XXI of his History of Rome from its foundation. The Carthaginian army confronts the hostile, indomitable mountains. The poet Silius Italicus, in his narrative Punica, also describes this terrifying quest. The Alps are described as a place of terror, the lair of the gods. Anyone daring to cross their sacred domain is exposed to the worst reprisals. The text depicts man's ceaseless struggle against nature, invincible and cruel.

In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder also refers to the Alps as a place of mystery. A threatening and impregnable wall, the mountains are populated by fierce men and form a natural barrier between civilizations. But in these remote times, mention of the Alps in literature was more a matter of historical testimony than poetry. Men saw them above all as an obstacle to their conquests, and danger was transformed into ugliness. For centuries, it was better to avoid them, not to contemplate them.

The Alps in literature: the menacing, fantastic mountain

The Alps are the backdrop for fantasy stories. In these isolated, inhospitable places, themes of fear and madness are exacerbated. In 1818, Mary Shelley set her creature in the Alps in Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. She describes the landscape of the Swiss Alps with such precision that the reader is transported to the heart of the action. When Victor Frankenstein confronts the monster he has brought to life, the omnipotence of the surrounding mountains is equal to the drama unfolding. On the Mer de Glace, the sheer size of the Alps amplifies the heroes' despair and anger: "The immense mountains and precipices that towered over me on all sides, the sound of the river raging among the rocks and the crash of the waterfalls all around, spoke of a power as formidable as that of omnipotence." In this dark, chimerical atmosphere, the mountain allows the author to distill terror in the reader's mind.

In 1925, it was the turn of Swiss writer Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz to describe the Alps as an implacable deity. In his novel La grande peur dans la montagne, he makes the mountain his evil heroine. Just as men threaten to invade, it suddenly decides to swallow them up: "It's that the mountain has its own will, it's that the mountain has its own ideas. The diabolical rulers of the summits are repeated in Derborence, written by Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz in 1934. In the Diablerets massif, a shepherd finds himself buried under the ice. Anxiety spreads throughout the story, as it does in the mountain pastures. The end of the world is near. The emptiness and silence of the high mountains provide an ideal frame setting for the author to describe death and rebirth.

Jean Giono's Batailles dans la montagne, published in 1937, also elevates the Alps to the status of a mythical figure, featuring a glacier as a prelude to death. Rejecting the corpses of men subjected to the will of merciless nature, the ice ogre portrays the Alps as a sinister, unfeeling god. Faced with this "Leviathan", mankind can only save itself by joining forces. A menacing shadow also hangs over the Dolomites, portrayed by Dino Buzzati in his first novel, Bàrnabo des montagnes, published in 1933. Although the hero eventually finds serenity there, for the author, the southern eastern Pre-Alps are the ideal frame setting for confrontation and devastation.

To end on an unusual note, writers sometimes play on the Alps to feed their readers' fantasies. In his Impressions de voyage, Alexandre Dumas recounts the expedition he led to Switzerland in 1832. With the art of a poet-dramatist, he recounts his stay at the Hotel de la Poste in Martigny. As he feasted on a tasty bear steak, he felt his stomach turn when the host announced bluntly about the bear: " This fellow ate half the hunter who killed him. In this literary anthology, the Alps remain the breeding ground for myth and the implausible.

Mountains from Petrarch to Rousseau: Awakening sensitivity to nature

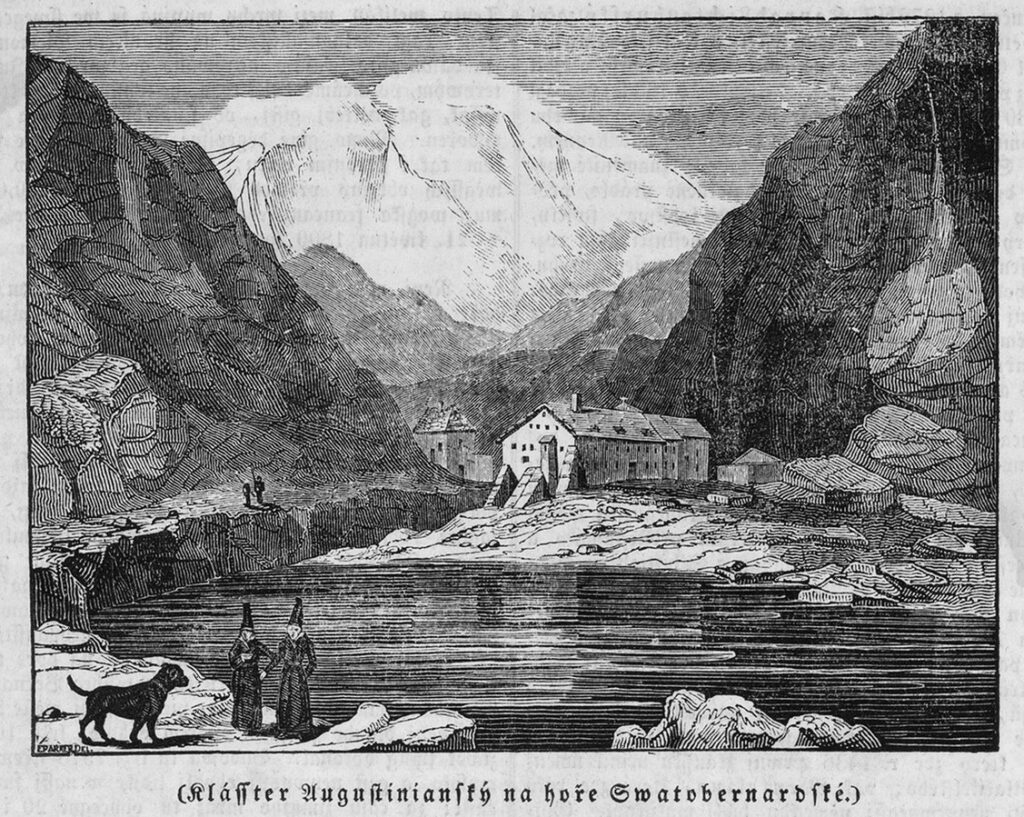

In 1336, Francesco Petrarch reinvented the link between mountains and literature. In his letter entitled L'ascension du mont Ventoux, the poet introduces us to the vertigo of contemplation. Although the journey he recounts takes place far from the Alps, his account marks the transition to a new era. More than a symbol of murderous dread, the mountain becomes for the writer the theater of a spiritual quest. Man awakens to nature, and literature to the world above. Petrarch did not climb Mont Ventoux out of necessity, but to find an answer to his divine aspirations. At summit, he marveled at the view before him. His gaze fascinated by the splendor of the landscape, he felt filled with the most intense emotions. Never before had the mountains appeared so prodigious in text. Taking advantage of the beauty of the setting, Petrarch opened Saint Augustine's Confessions: " Men go off to admire the peaks of the mountains, the waves of the sea, the vast course of the rivers, the circuits of the ocean, the revolutions of the stars, and they forsake themselves. " With these words, he begins to reflect on the futility of men and their mad desires. This paved the way for Romanticism and the quest for the sublime.

It wasn't until the 18th century, however, that the flame lit by Petrarch finally caught fire in literature. Scientists, artists and explorers began to develop a passion for the Alps. The first Swiss writer to pay tribute to the Alps in his work was Albrecht von Haller. In 1729, his poem Die Alpen spread throughout Europe as an ode to the high mountains. In his verses, no monstrous shadows but the magnificence of a world still unknown to his contemporaries. Opposing the classical ideal of civilization to the grandiose nature of the Alps, he reaches out to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the illustrious precursor of Romanticism.

Born in Geneva, Jean-Jacques Rousseau grew up between mountains and valleys. He explored the Alps and saw summits as an ideal place for contemplation. Moved by their immense beauty, he celebrated nature as a return to his roots. His epistolary novel Julie ou la nouvelle Héloïse, published in 1761, marks a decisive turning point in the reader's image of the high mountains. Vibrant and profound, her words transport us to the highest summits of the Alps. To find refuge, to find peace. To soar towards serenity. Under Rousseau's pen, the mountains are transformed into a new Eden: " It seems that by rising above the abode of men, one leaves behind all base and earthly sentiments, and that as one approaches the ethereal regions, the soul contracts something of their unalterable purity. "(The New Heloise, Letter XXIII).

The time has now come to open the doors to Romanticism. frame of ecstasy and dazzlement, the Alps will be sung by poets and writers.