Matterhorn, July 14, 1865: a tragic first

If it is today one of the most climbed mountains of the Alps every year, the Matterhorn has long resisted attempts to climb it: it was one of the last mountains to be climbed and considered, with the grandes Jorasses and l'Eigeras one of the last three problems of the Alps. The first ascent of the Matterhorn dates back to July 14, 1865.

Rivalries and stakes

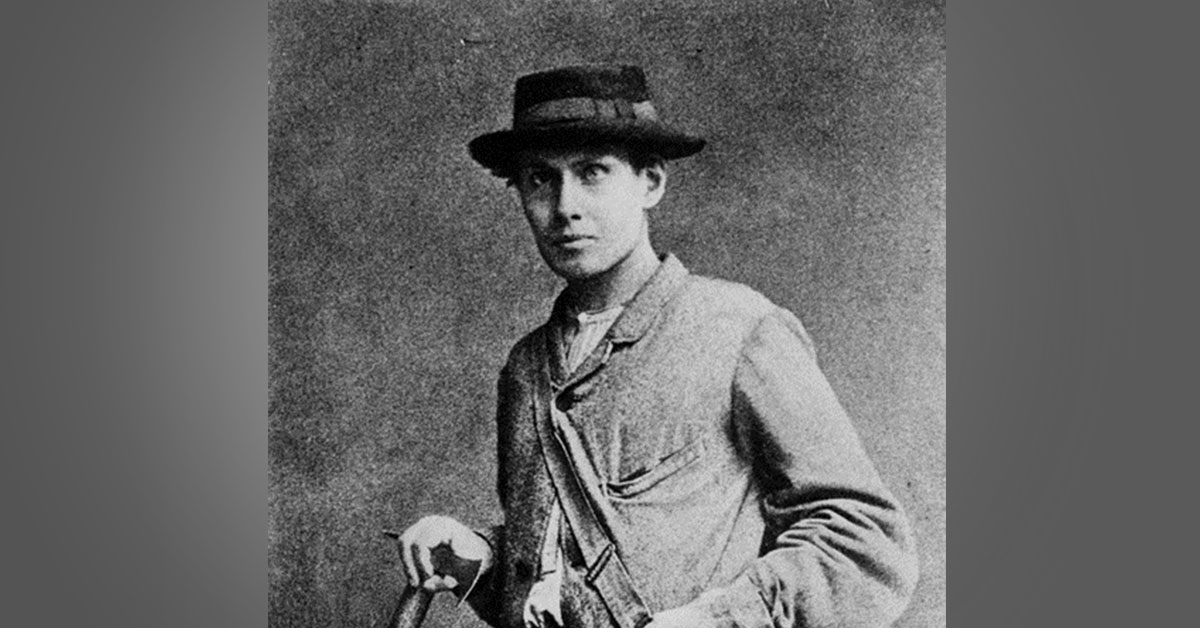

Many people wanted to be the first to walk on the Matterhorn summit . Two in particular: the Englishman Edward Whymper and the Italian mountain guide Jean-Antoine Carrel. After six unsuccessful attempts, Whymper hired Carrel for a new attempt, on the Italian side, which was then considered the least difficult.

But Carrel was playing a double game and had made a commitment to his compatriots: they wanted the Matterhorn to be an Italian premiere - nationalism and mountaineering had gone hand in hand for several years. With a Matterhorn premiere, they wanted to mark the recent Italian independence.

A rope of circumstance

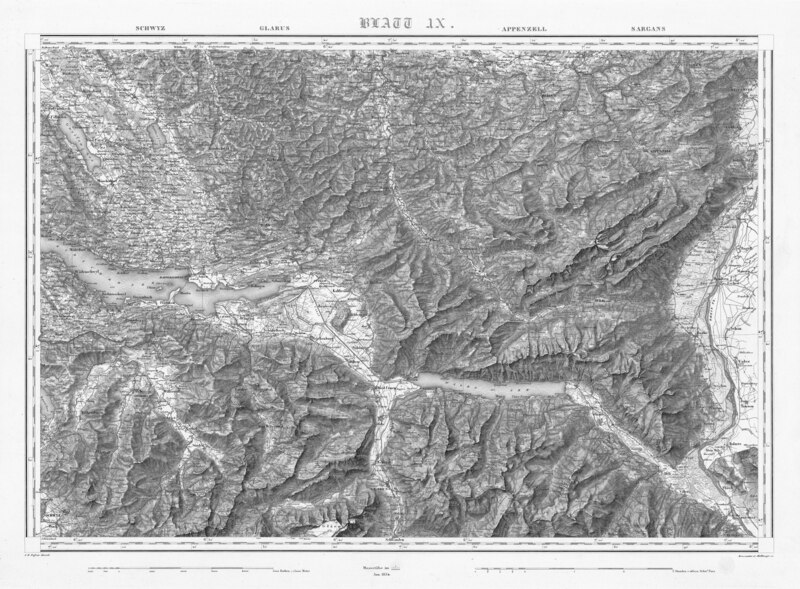

Carrel having made him jump, Whymper found himself without a guide and short of time. It was then that he met Lord Francis Douglas, a relative of Queen Victoria, who also dreamed of climbing the Matterhorn. He knew the Taugwalder guides, father and son, both named Peter, from previous mountain trips. The four men decided to climb the Matterhorn the next day, starting from Zermatt.

Douglas and Whymper stayed at the Hotel Monte Rosa, where they met the Reverend Charles Hudson, an accomplished mountaineer, as well as his protégé, the young Douglas Hadow, and their guide, the Chamonix native Michel Croz, whom Whymper had beaten a few days earlier on the first ascent of the Aiguille Verte. As the three men had planned to climb the Matterhorn by the Hörnli the next day, it was decided to make only one team. In the end, it was a heterogeneous group of climbers, formed by interest and circumstance, who set out to climb the Matterhorn in the early morning of July 13. Hadow is the least experienced, he has only one real ascent in the Alps to his credit.

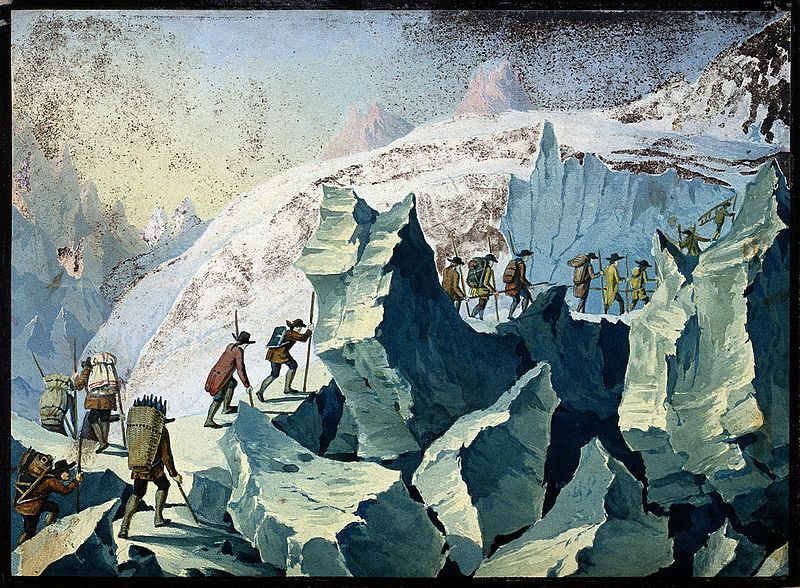

The ascent

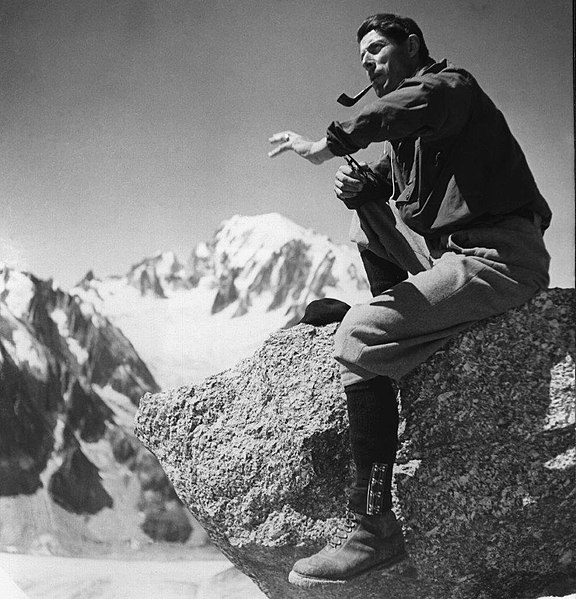

The 13th of July went smoothly, Whymper and his companions were even surprised to find that the climb was easier and faster than expected. On the other side, Carrel and his men advance more slowly, not suspecting that competitors have been attempting the ascent since Zermatt. Whymper and his companions slept in the evening about 200 meters above the current Hörnli hut. They set off again on the 14th and did not encounter any major difficulties before the shoulder, a tricky passage which led them to decide to go up the north face.

Finally, the summit is in sight, within reach. It is then that Whymper disengages himself to be sure to be the first to reach summit. He is closely followed by Michel Croz. The two men then saw Carrel and his men below on the Italian side. Whymper called out to them to warn them that they had lost the race, but they did not hear him. He then threw stones to attract their attention... Disappointed at having been beaten, the Italians turned back.

The descent and the fall

The men stay for about an hour at summit. Then Croz, Hadow, Hudson and Douglas begin the descent, in that order. Taugwalder Sr. follows later, and finally Taugwalder Jr. and Whymper, who lingers at summit to draw and take some notes; he also writes on a sheet of paper that he puts in a bottle his name and that of his companions. Taugwalder and Whymper then rope up with their companions.

Croz was following in the footsteps of Hadow, the less experienced man. But it was Hadow who slipped first, dragging Croz, Hudson and Douglas down with him. The small rope linking these four men to Taugwalder and Whymper broke. It was a fatal fall. It is about 3:10 pm. The survivors are stunned and only recover after many minutes. They will reach Zermatt only the next day, after having spent another night on the wall.

A story of rope(s)

Searches conducted immediately after the return of the Taugwalders and Whymper found body parts of Croz, Hadow , and Hudson ; Douglas' body was never found. The survivors were accused of cutting the rope that connected them to the fallen men, but the trial that followed the tragedy found no conclusive evidence, and Whymper and the Taugwalders were acquitted.

In Scrambles among the Alpsin which he recounts his many ascents and first ascents in the Alps, Whymper charges Taugwalder Sr. with using a weaker rope to rope up Douglas, the last of the four men who had started the descent first. The seven men actually had two ropes at their disposal: a classic one, with low resistance, and a new one, made available by the Alpine Club of London.

In fact, it seems that Peter Taugwalder had no choice: in order to free himself from the rope and reach summit first, Whymper would have cut the Alpine Club rope. The two halves of the rope - the first half linking Croz, Hadow, Hudson and Douglas, the second half linking Taugwalder father, Whymper and Taugwalder son - were not enough to rope everyone up, so Taugwalder had no choice but to use the second rope to rope up Douglas.

Consequences and repercussions

The Matterhorn disaster caused a great scandal in Europe, all the European press talked about it. The scandal was particularly important in England, so much so that Queen Victoria thought of forbidding climbing to her compatriots, before changing her mind. But this also ended up giving the Matterhorn international fame, and attracted many tourists to Zermattwanting to see the summit where such a tragedy took place.

The tragic first ascent of the Matterhorn is considered to be the event that marked the end of the golden age of mountaineering - the 1850s and 1860s. It was during this period that the majority of summits over 4000 meters were climbed for the first time.

Let's conclude this article with Lucy Walker, who was the first woman to have successfully climbed the Matterhorn, on July 22, 1871.