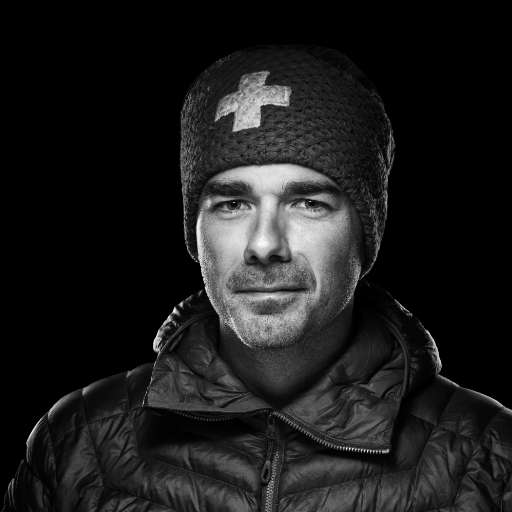

Internationally renowned visual artist and photographer Jacques Pugin is constantly pushing back the boundaries of photography. A precursor of light painting from the late 1970s onwards, his work is now part of a post-photographic approach. But here again, Jacques Pugin surprises, breaking the codes of contemporary production. He superimposes, recomposes, experiments and mixes techniques to invent his own way of depicting the world. Through his work, he explores man's relationship with the passage of time and his environment. An encounter with an avant-garde photographer who frees himself from the constraints of the tool to touch the very essence of his art, paying dazzling tribute to the world around him.

The art of Jacques Pugin | Playing with lines and light

Let's start by talking about your career as an artist. How did you become a photographer?

For me, creating has always been a matter of course. I feel closer to a painter or sculptor than to a photographer. I was one of the first photographers to receive a fine arts scholarship, at a time when photography was not recognized as it is today. For me, being an artist was more a matter of necessity than choice. Creating was essential to my equilibrium. I left my parents at 18 to take up photography, and art has never left me.

Commenting on your 1979 series Graffiti Greffés, journalist Christian Caujolle looks back at the etymology of the term photographer, one who "writes with light". What is your relationship with light in your art?

For me, light is a means of writing, allowing me to inscribe my passage in the image by emphasizing certain aspects of the landscape. Without realizing it, I embarked on a form of Land art. I began by occupying space with a 5-metre rope in 1978. Then I felt the need to inhabit nature more freely. That's when I came up with the idea of the luminous trace. That's how I became a pioneer in the art of light painting. In the Graffiti Greffés and Graffiti rouges series, I used the flame of a candle like a pencil. As the light followed the current of the river on which I sailed, I photographed the inexorable passage of time. And the lines of light that run through my work reflect man's imprint on nature, just as the photographer models reality. In my art, I speak of the passage of time as the trace that man leaves on nature. The two notions are inextricably intertwined.

In your work, you explore both black & white and color. Which prism do you feel most closely linked with, and what does it say about your art?

My choice essentially depends on the nature of the project I'm working on. I arrange the shades in my own way to bring out certain elements of the landscape. I switch from color to black and white, from positive to negative. The form the work takes is adapted to the theme I'm dealing with, the emotions I want to convey and the aesthetic I wish to convey.

Jacques Pugin and the Alps | From Blue Mountain to Shadow Mountain

In the Blue Mountain series, you honor the most famous summits of the Alps. What do these works reveal about the mountains?

Here, I remodel the mountain in my own way, with a play of shapes and colors. We're in the 1990s, and these works created from videos were printed at home using the technology available at the time. The approach was pictorial. I made the mountains my own, giving them a more personal aspect. Painting mountains allowed me to leave my mark on them. These images carry with them an element of mystery. More than the essence of the mountain, they reveal my link with this nature that is so close to me, and my way of making it my own.

In the series La montagne s'ombre, rather than highlighting immaculate nature, you seem to reveal the essence of the mountain through the use of graphics Powerful. What do these works ultimately convey?

Accentuating the mountain shadows was a way for me to sublimate the landscape. A way of emphasizing certain elements of the image. A way of repainting the mountain as a work of art. The graphics and aesthetic strength of these creations accentuate the majesty of summits. To highlight the mountain's features while making them my own. Reshaping nature to give life to a much more personal aspect of the mountain. Beyond photography as a vector of reality, I work on the image, within the image, to metamorphose it into a unique work that corresponds to me. The images we make always correspond to us, of course, but by this I mean that my approach is closer to that of a visual artist than that of a photographer. I accentuate, I underline, I attenuate, I model to sublimate reality, to make it different. Photography is a material I rework, a tool I use to give meaning to my art.

Spotlight on The Matterhorn | When nature becomes an artist

Your Day after day project is dedicated to The Matterhorn. What does this mythical mountain in the Swiss Alps mean to you, and what role does the mountain play in your art?

For me, the Matterhorn is one of the most beautiful mountains in the world. Its pyramidal shape is exceptional. The graphic lines are unique. It's highly photogenic and instantly recognizable. The Matterhorn is the very symbol of the mountain and a very inspiring model for me as an artist.

I love extreme landscapes, deserts and mountains. Of course, I have a special bond with the Alps, because I grew up surrounded by them. They are a natural source of inspiration for me. I don't think my art particularly highlights the grandeur of the mountains. It doesn't convey the majesty of the Alps. But I use the mountains as a creative subject, a means of expression that, over time, nourishes my art.

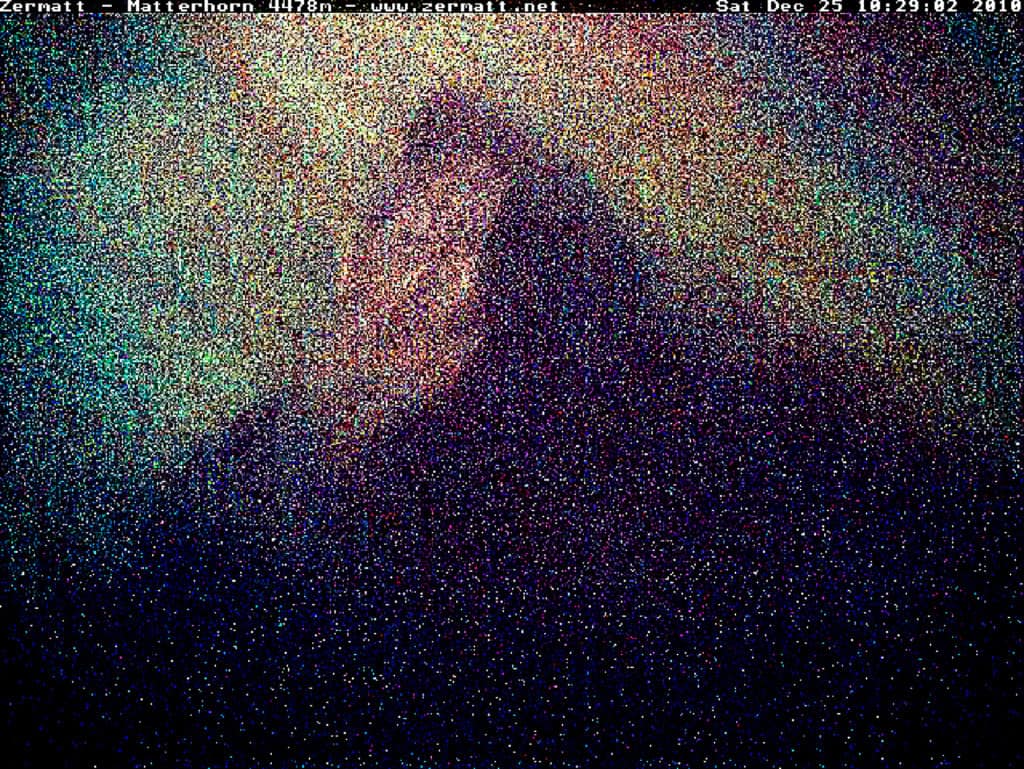

To carry out this project, you recorded daily images of the Matterhorn from a webcam located at Zermatt . Hélène Beade describes this incredible body of work as a palimpsest. How do you see the place of nature and your role as an artist in the birth of these works?

Nature is the artist of this project. The Matterhorn disappears into the clouds, turns white, is draped in black and plays with light. Over time, nature transforms the mountain as an artist would. She sculpts and depicts it. It's up to me to honor it by adding my own filters to the work. By selecting and arranging the images, magnifying the pixels that make up the shots, delivering to the eye the mountain redrawn by pointillism. And then, here again, I wanted to transcribe through my art the ineluctable power of time passing. For me, freezing the ephemeral is a way of marking time, of imprinting it so as to retain it better. Even if nature continues to evolve.

Facing climate change | A photographer's view of mountain evolution

You have produced two photographic series on the theme of glaciers. Your work reveals the irony of men trying to slow down the disappearance of glaciers to serve their own interests. At the same time, it highlights the splendor of glaciers, their history and the tragedy of their destiny. How do you see the role of the artist in the face of climate disruption and the changes taking place in the high mountains?

In the Glaciers series, I follow the trail of a man desperately trying to slow down the melting ice. Underneath the theatrical aspect of this rescue, the stakes are financial. Every year, tourists flock to the Rhone glacier to discover its beauty. Illusory survival. But, for me, this work is not complete. These photos simply bear witness to a reality without any subsequent artistic remodeling. It's like the end of the world, a snapshot of the drama unfolding. The disaster is so blatant that it stands on its own, sweeping us off our feet. I went back this summer with Thomas Crauwels on the Mer de Glace and it's a catastrophe. The ice now mingles with the gravel, when it hasn't given way to boulders. We went back up to the Géant glacier to see the last vestiges of heat-resistant ice. But their time is running out.

My first photographic series on glaciers allowed me to evoke the proximity of their disappearance. Then, in the following series, Glaciers Offset, I try to bring them back to life. After acknowledging their decline, I use images to go back in time. From raw, the photograph is transformed. The works come from my imagination. I created these works from videos shot by drone over glaciers. By superimposing the shots, by transparency, by montage, my art results in their reconstruction. Through the dynamism of the works, the glaciers seem to be reborn, their history resurfacing and their beauty becoming visible again. For me, it's not a question of retranscribing reality. There's no such thing as an objective image. It's about conveying my own vision of glaciers, of what makes them what they are, of their history and their future. I use video and photography to paint the world, to construct a personal work of art.

In one of your most recent bodies of work, La montagne assiégée, you denounce mass tourism, mountains disfigured by man, pollution and over-consumption. Here, color stains rather than illuminates, stings rather than caresses. Do you think art can help reveal consciences?

I don't see my work as a direct testimony to how the world is changing. Unlike photojournalistic snapshots, my work does not directly engage the viewer. The composition is approached through a double reading. As an artist, I remodel the raw image, capturing it before reconstructing it. I imagine by playing with shapes and colors. I use photography like a visual artist, repainting and transforming it. I allude to subjects that touch me without really announcing it. As for the viewer, he or she is first struck by the aesthetics of the work before entering into reflection. Understanding follows perception. So, yes, my works do make you think, and alert you to themes that are close to my heart, but indirectly, by touches, by triggers.

Jacques Pugin exhibits his work all over the world and continues to venture further and further into creation, experimenting with materials and tools as his inspiration takes him to the most dazzling frontiers of his art.